Pivô Satélite / A conversation with the artists of the 3rd edition of the project

Since 2020, the Pivô Satellite digital platform presents works by artists selected by a group of three young guest curators. Each curator chooses four artists who will create an individual work to be exhibited on the digital platform for one month. In addition to the quality of artistic research, the selection takes into account aspects such as gender diversity, ethnicity, race, background, and social and cultural contexts.

Aiming to contribute to the creation of a support network for the artistic community, the initiative invites artists to present experimental projects that can take on different formats, themes, and media. Opening on 9th July, the 3rd edition, entitled 'Sexo, Mentiras e Videotape' (Sex, Lies, and Videotape) is curated by Raphael Fonseca. To find out first-hand what to expect from the projects, we interviewed the four artists participating in the 3rd edition, Eduardo Montelli, Laura Fraiz, New Memeseum, and Ventura Profana.

EDUARDO MONTELLI (Porto Alegre / RS, 1989)

Visual artist. Doctor in Visual Arts, PPGAV/EBA/UFRJ. In his artistic and theoretical research, Eduardo investigates the influence of documents, narratives, and other forms of 'inscription of the self' on how people live and are socially recognized. Since 2009, Eduardo has participated in exhibitions and other art activities, such as Prêmio Energias na Arte 5th Edition, at Instituto Tomie Ohtake, São Paulo; Filmes e Vídeos de Artistas, at the Iberê Camargo Foundation, Rio Grande do Sul; Abre Alas 10, at the gallery A Gentil Carioca, Rio de Janeiro; and 65th Salão de Abril, at Centro Cultural Banco do Nordeste, Ceara, in which his video 'Fundos' received an award. In 2019, he presented the solo exhibition 'Como faremos para desaparecer' (How we will do to disappear), curated by Charlene Cabral, at the gallery of the ECARTA Foundation, in Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul. In 2020, he was one of the artists nominated for the PIPA Award.

Visual artist. Doctor in Visual Arts, PPGAV/EBA/UFRJ. In his artistic and theoretical research, Eduardo investigates the influence of documents, narratives, and other forms of 'inscription of the self' on how people live and are socially recognized. Since 2009, Eduardo has participated in exhibitions and other art activities, such as Prêmio Energias na Arte 5th Edition, at Instituto Tomie Ohtake, São Paulo; Filmes e Vídeos de Artistas, at the Iberê Camargo Foundation, Rio Grande do Sul; Abre Alas 10, at the gallery A Gentil Carioca, Rio de Janeiro; and 65th Salão de Abril, at Centro Cultural Banco do Nordeste, Ceara, in which his video 'Fundos' received an award. In 2019, he presented the solo exhibition 'Como faremos para desaparecer' (How we will do to disappear), curated by Charlene Cabral, at the gallery of the ECARTA Foundation, in Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul. In 2020, he was one of the artists nominated for the PIPA Award.

Eduardo Montelli. Film still of we are making art, 2019.

[TT]

The use of everyday objects and the removal of their context, in a way, guide your production. How is your relationship with such objects? How do you understand the displacement of them from their commonplace?

The use of everyday objects and the removal of their context, in a way, guide your production. How is your relationship with such objects? How do you understand the displacement of them from their commonplace?

[EM]

I started using some everyday objects right at the beginning of my artistic experiments. That process arose spontaneously, largely because of the objects themselves, the way we relate to them, and the meanings we create for these relationships. First, I chose (intuitively) to treat the domestic environment, the house, as an art 'object' of thought and action. Then, I started to observe this environment's 'contents.' In the land where my family has lived for more than 50 years, there is a place we call a 'shed,' a type of warehouse crammed with furniture and other household items that we no longer use but which we do not want to donate or throw away because we may need them at some point. We ended up accumulating these objects across generations, and suddenly, I find myself inside the shed wanting to use them again, but this time with an artistic intention. I think that the 'shed' is a kind of sculpture or collective installation selflessly built by my family - I like to imagine a large expanding work made up of all the 'sheds' of all the families in the street, in the neighborhood, in the city. Anyway, this practice of storing objects is, at the same time, personal and collective. It is private and individual but also shared by a lot of people; it is cultural. I am not so interested in displacing these objects to art environments, such as the readymades. I am more interested in their presence and meaning in everyday life, outside the official art framework. That is why, when I do an exhibition, I work more with archives than with the objects themselves. Through performances, photographs, videos, gifs, and texts I produce in my daily engagement with these places and objects, I try to make a type of documentary work that addresses precisely this relationship between the subject and its environment. It is a small and fragile attempt to observe and find meanings for a world so big, changing, and full of things. Every time one of these objects appears in some artistic process, I think I am finding a new use for it, more specifically, one that dialogues with 'artistic' ideas. This gesture is linked to an entire thought about the possibility of everyday life as an art experience, which is perfectly summarized in Oiticica's phrase 'the museum is the world.' Finally, I realized that the logic of accumulation and the constant attempt to find new uses and new compositions for objects, in a way, works as a methodology in my artwork, as the images produced also become stored objects. In this case, they are digital files accumulated in HDs and clouds, from which I can set up exhibitions in galleries, for example.

I started using some everyday objects right at the beginning of my artistic experiments. That process arose spontaneously, largely because of the objects themselves, the way we relate to them, and the meanings we create for these relationships. First, I chose (intuitively) to treat the domestic environment, the house, as an art 'object' of thought and action. Then, I started to observe this environment's 'contents.' In the land where my family has lived for more than 50 years, there is a place we call a 'shed,' a type of warehouse crammed with furniture and other household items that we no longer use but which we do not want to donate or throw away because we may need them at some point. We ended up accumulating these objects across generations, and suddenly, I find myself inside the shed wanting to use them again, but this time with an artistic intention. I think that the 'shed' is a kind of sculpture or collective installation selflessly built by my family - I like to imagine a large expanding work made up of all the 'sheds' of all the families in the street, in the neighborhood, in the city. Anyway, this practice of storing objects is, at the same time, personal and collective. It is private and individual but also shared by a lot of people; it is cultural. I am not so interested in displacing these objects to art environments, such as the readymades. I am more interested in their presence and meaning in everyday life, outside the official art framework. That is why, when I do an exhibition, I work more with archives than with the objects themselves. Through performances, photographs, videos, gifs, and texts I produce in my daily engagement with these places and objects, I try to make a type of documentary work that addresses precisely this relationship between the subject and its environment. It is a small and fragile attempt to observe and find meanings for a world so big, changing, and full of things. Every time one of these objects appears in some artistic process, I think I am finding a new use for it, more specifically, one that dialogues with 'artistic' ideas. This gesture is linked to an entire thought about the possibility of everyday life as an art experience, which is perfectly summarized in Oiticica's phrase 'the museum is the world.' Finally, I realized that the logic of accumulation and the constant attempt to find new uses and new compositions for objects, in a way, works as a methodology in my artwork, as the images produced also become stored objects. In this case, they are digital files accumulated in HDs and clouds, from which I can set up exhibitions in galleries, for example.

[TT]

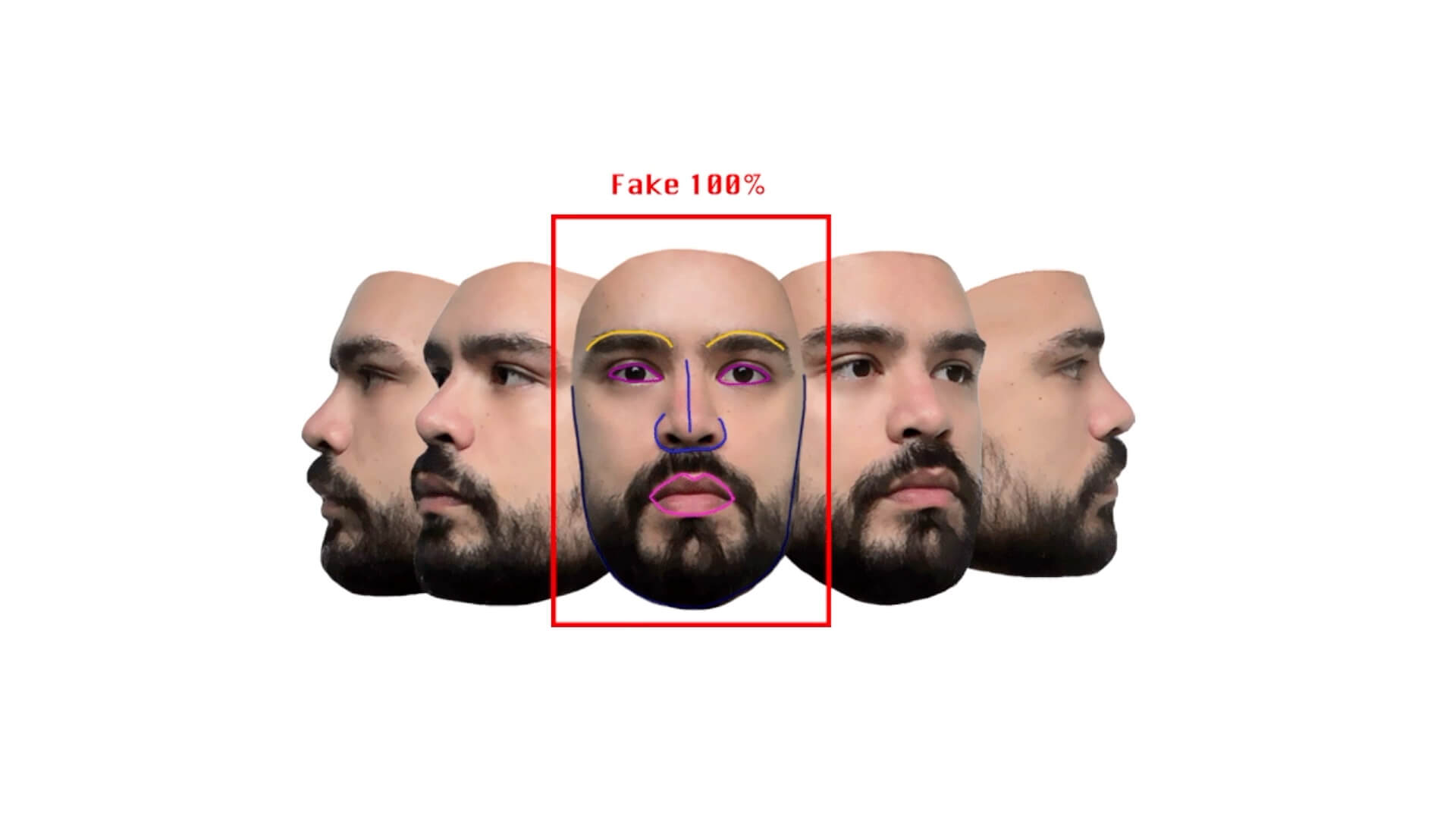

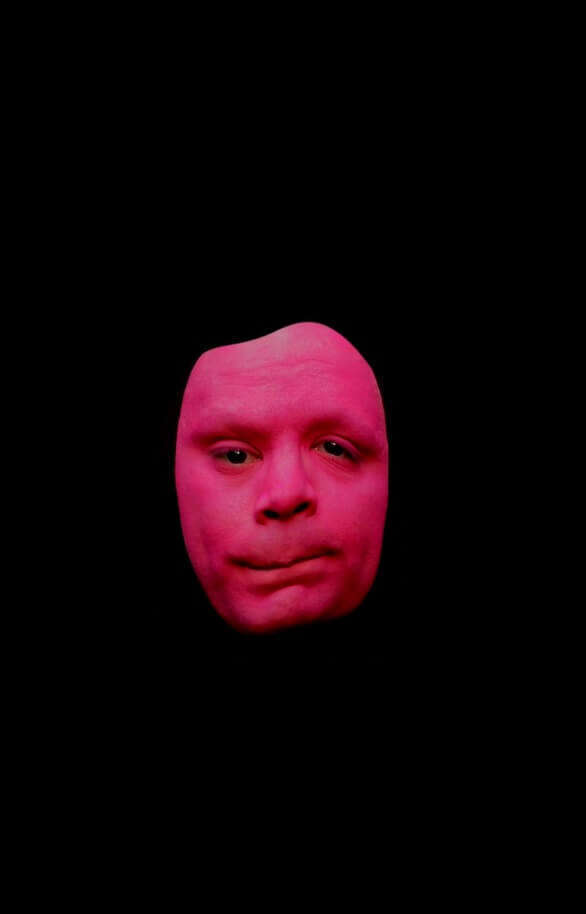

Your production speaks a lot about the body's presence and dissolution, understanding as a matter that operates in everyday life. Tell us a little about your research on the body and its consequences. [EM] The 'body' is also an 'object' that has interested me since my first works. In 2008, inspired by the discovery of the works of Diane Arbus, Robert Mapplethorpe, and Nan Goldin, which portray bodies outside society's normative standards, especially concerning gender, I took some photographs of my mother, who is a lesbian and has a masculine appearance. That same year, after watching Pina Bausch's film O Lamento da Imperatriz, I started performing for photography and video, usually in my house's courtyard. So, along with the 'objects,' I reflect about the body, about my own body, and about the body of the other - a body that is also an object accumulated in the world, a body that is also an image projected on the world. I think of the 'body' (object or image) as a permanent construction guided by normative models. Most of the images I have produced using my body (or other people's bodies) are like comments about these models, about their effects on our lives, about their modes of reproduction and subversion. I understand that the bodies' 'plasticity,' their ability to be 'shaped' by gestures and images, serves both normativity and creativity. The figure of the 'mother' appears in my work as a recognition of the bodies already in the world before us and through which our existence becomes possible. The fact that my mother identifies herself as 'lesbian' and 'male' raises more questions. Her participation in my artistic process goes beyond thinking about the body, as it problematizes social norms of sexuality, gender, and parenting. In my work, there is an idea of disjunction between the body and the social but, at the same time, there is space for invention and experimentation, freedom, desire to create links with other bodies beyond images. I try to think in a non-dualistic, non-binary way, trying to understand the multiplicities, the complexities, and mainly the movements of transformations of a body in the world. I made a video called 'Chiclete' (Gum) in 2020, in which my face appears distorted and painted pink, suggesting the shape of a discarded chewing gum in a dark, empty space. In this video, the image of the 'body' appears isolated, reduced, deformed, and objectified. In a series of works comprising my mother's first portraits to 'Chiclete,' I see a kind of narrative of formation (or deformation) that remains open. More than revealing an exemplary life story, this narrative talks about the ups and downs of the body's experience over the world, one that projects objects and images over a world.

Your production speaks a lot about the body's presence and dissolution, understanding as a matter that operates in everyday life. Tell us a little about your research on the body and its consequences. [EM] The 'body' is also an 'object' that has interested me since my first works. In 2008, inspired by the discovery of the works of Diane Arbus, Robert Mapplethorpe, and Nan Goldin, which portray bodies outside society's normative standards, especially concerning gender, I took some photographs of my mother, who is a lesbian and has a masculine appearance. That same year, after watching Pina Bausch's film O Lamento da Imperatriz, I started performing for photography and video, usually in my house's courtyard. So, along with the 'objects,' I reflect about the body, about my own body, and about the body of the other - a body that is also an object accumulated in the world, a body that is also an image projected on the world. I think of the 'body' (object or image) as a permanent construction guided by normative models. Most of the images I have produced using my body (or other people's bodies) are like comments about these models, about their effects on our lives, about their modes of reproduction and subversion. I understand that the bodies' 'plasticity,' their ability to be 'shaped' by gestures and images, serves both normativity and creativity. The figure of the 'mother' appears in my work as a recognition of the bodies already in the world before us and through which our existence becomes possible. The fact that my mother identifies herself as 'lesbian' and 'male' raises more questions. Her participation in my artistic process goes beyond thinking about the body, as it problematizes social norms of sexuality, gender, and parenting. In my work, there is an idea of disjunction between the body and the social but, at the same time, there is space for invention and experimentation, freedom, desire to create links with other bodies beyond images. I try to think in a non-dualistic, non-binary way, trying to understand the multiplicities, the complexities, and mainly the movements of transformations of a body in the world. I made a video called 'Chiclete' (Gum) in 2020, in which my face appears distorted and painted pink, suggesting the shape of a discarded chewing gum in a dark, empty space. In this video, the image of the 'body' appears isolated, reduced, deformed, and objectified. In a series of works comprising my mother's first portraits to 'Chiclete,' I see a kind of narrative of formation (or deformation) that remains open. More than revealing an exemplary life story, this narrative talks about the ups and downs of the body's experience over the world, one that projects objects and images over a world.

Eduardo Montelli. Minha mãe, photography, 2008.

[TT]

Tell us a little about your ideas for the Pivô Satellite project, what are your plans? [EM] I am thinking of the Pivô Satellite website as an empty room that I was invited to occupy. I intend to work in this room during the entire project making daily posts. I want to do something similar with the collages by the German artist Kurt Schwitters, especially with the remaining photographs of the work 'Merzbau,' destroyed in World War II. 'Merz' is a word the artist found in a torn piece of newspaper, a fragment of the name 'Commerzbank.' So, 'Merzbau' means something like 'Merz construction.' For more than 20 years, Schwitters has made collages on the walls of the apartment he lived with his family, using the remains of texts, images, and objects found in the streets. This great installation collage in a domestic setting was the 'Merzbau,' or the 'Cathedral of Erotic Misery,' as it was also known. It is interesting to note that the 'Merzbau' is composed of volumes, recesses, subdivisions, nooks, in short, a series of ingenious experimentations of forms of spatialization. I want to use my digital image file as if it were Schwitters' collection of everyday fragments. And, with these images, I want to make 'modules' compositions in vertical GIF format (mobile screen standard), inspired by Merzbau's experimental spatialization. I think that each new 'module.gif' will be an occupation of a part of Pivot Satellite 'space.' The modules will be placed one above the other as if they were floors or rooms in a building. On the last day of work, we will have a 'building' of GIFs occupying a lot of space, which can be seen in full by scrolling the page. I already have the title: Só sei me transformar, apenas não sei em que (I only know how to transform myself, I just don't know in what).

Tell us a little about your ideas for the Pivô Satellite project, what are your plans? [EM] I am thinking of the Pivô Satellite website as an empty room that I was invited to occupy. I intend to work in this room during the entire project making daily posts. I want to do something similar with the collages by the German artist Kurt Schwitters, especially with the remaining photographs of the work 'Merzbau,' destroyed in World War II. 'Merz' is a word the artist found in a torn piece of newspaper, a fragment of the name 'Commerzbank.' So, 'Merzbau' means something like 'Merz construction.' For more than 20 years, Schwitters has made collages on the walls of the apartment he lived with his family, using the remains of texts, images, and objects found in the streets. This great installation collage in a domestic setting was the 'Merzbau,' or the 'Cathedral of Erotic Misery,' as it was also known. It is interesting to note that the 'Merzbau' is composed of volumes, recesses, subdivisions, nooks, in short, a series of ingenious experimentations of forms of spatialization. I want to use my digital image file as if it were Schwitters' collection of everyday fragments. And, with these images, I want to make 'modules' compositions in vertical GIF format (mobile screen standard), inspired by Merzbau's experimental spatialization. I think that each new 'module.gif' will be an occupation of a part of Pivot Satellite 'space.' The modules will be placed one above the other as if they were floors or rooms in a building. On the last day of work, we will have a 'building' of GIFs occupying a lot of space, which can be seen in full by scrolling the page. I already have the title: Só sei me transformar, apenas não sei em que (I only know how to transform myself, I just don't know in what).

Eduardo Montelli. Film still of Chiclete, 2020.

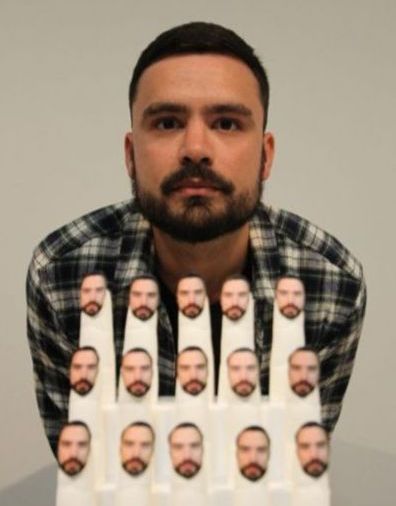

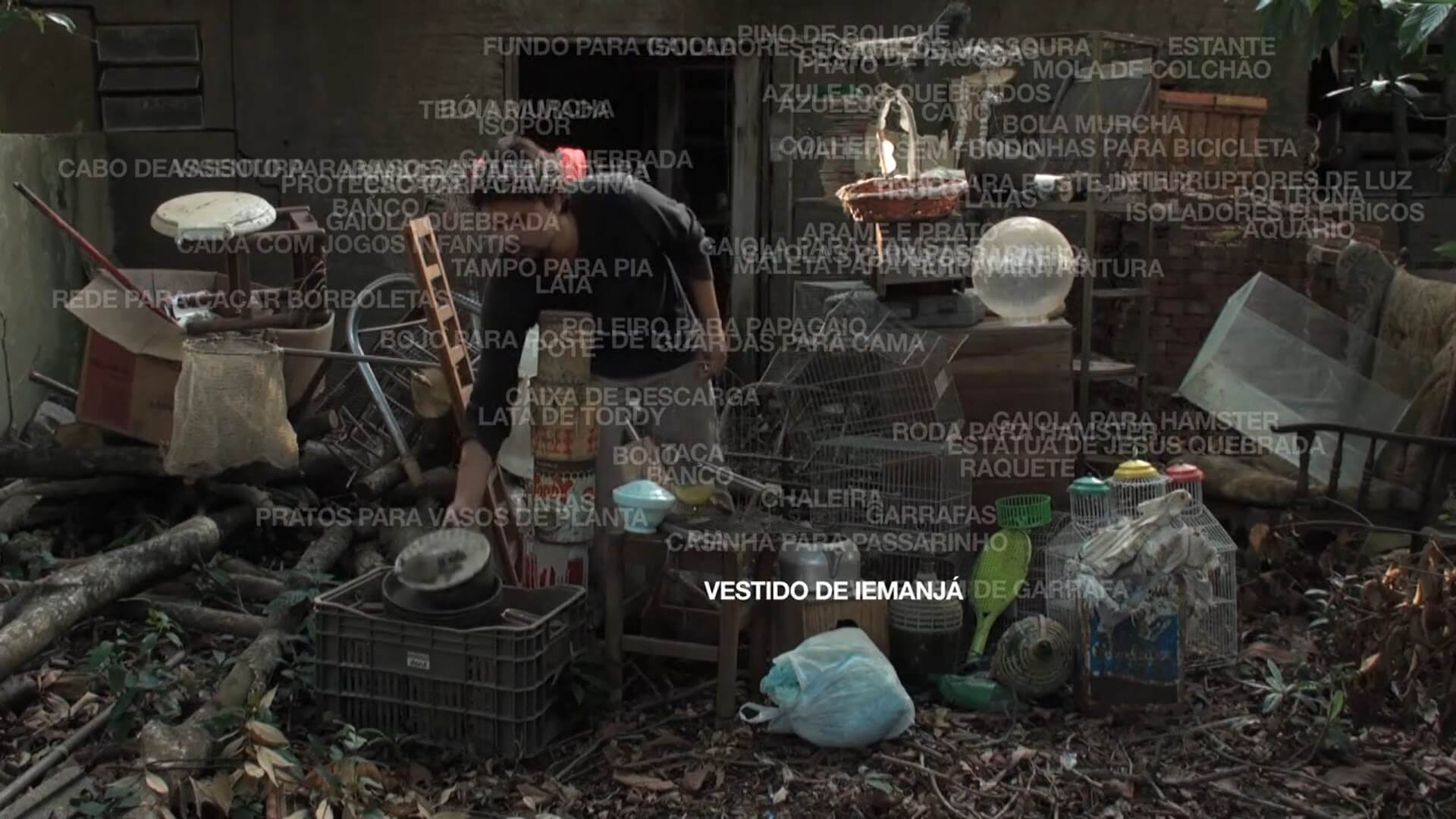

Eduardo Montelli. Film still of Fundos, 2013.

LAURA FRAIZ (São Paulo / SP, 1996)

Laura is a Brazilian and Venezuelan artist who works with video, performance, drawing, painting, sound, and writing. Her production centers on creating confessional and autobiographical narratives, exposing memories, secrets, and daydreams to investigate relationships between reality and fiction, violence and desire, control, and disobedience. Graduated in Visual Arts from the University of Brasília, she exhibited her work across Brazil, in Switzerland, and Singapore. In 2018, she was awarded the Transborda Brasília Award for the videos Mordente (2017) and Inside My Baby (2006).

Laura is a Brazilian and Venezuelan artist who works with video, performance, drawing, painting, sound, and writing. Her production centers on creating confessional and autobiographical narratives, exposing memories, secrets, and daydreams to investigate relationships between reality and fiction, violence and desire, control, and disobedience. Graduated in Visual Arts from the University of Brasília, she exhibited her work across Brazil, in Switzerland, and Singapore. In 2018, she was awarded the Transborda Brasília Award for the videos Mordente (2017) and Inside My Baby (2006).

Laura Fraiz. Film still of No Es Una Novela.

[TT]

The presence of your body is a significant part of your research; you seem to place yourself between reality and fiction in creating your work. How do you create narratives from your image? How do you see the identity issue in this context? To what extent does autobiography appear?

The presence of your body is a significant part of your research; you seem to place yourself between reality and fiction in creating your work. How do you create narratives from your image? How do you see the identity issue in this context? To what extent does autobiography appear?

[LF]

My research takes place at the intersection between this reality and my private soap opera. I walk through the streets daydreaming with dramatic scenes where I am the lead actress; I exist in the world as if I were being filmed. My desire to expose and insert my body into the works comes from the alternation between me and someone else – sometimes a villain, some others a victim. I found in video art a place where these forces predominate and make it happen according to your wishes. I film myself to create true testimonials for this novel, transposing fantasy into a material reality that I can share. I need it to exist not only in my head. My work is not completely autobiographical but autofictional - a tangle of truths and lies articulated through juxtaposed images.

My research takes place at the intersection between this reality and my private soap opera. I walk through the streets daydreaming with dramatic scenes where I am the lead actress; I exist in the world as if I were being filmed. My desire to expose and insert my body into the works comes from the alternation between me and someone else – sometimes a villain, some others a victim. I found in video art a place where these forces predominate and make it happen according to your wishes. I film myself to create true testimonials for this novel, transposing fantasy into a material reality that I can share. I need it to exist not only in my head. My work is not completely autobiographical but autofictional - a tangle of truths and lies articulated through juxtaposed images.

[TT]

Themes such as violence, oppression (which is also a type of violence), and death are present in his production, explicit or not, sometimes in an ironic tone. I see the way you articulate these themes as one of the great powers of your work. How does the conception from idea to realization take place?

Themes such as violence, oppression (which is also a type of violence), and death are present in his production, explicit or not, sometimes in an ironic tone. I see the way you articulate these themes as one of the great powers of your work. How does the conception from idea to realization take place?

[LF]

I always start from a real discomfort inflicting me at that specific moment. It can be the fear of dying and being forgotten, the anger I feel at disgusting men, or jealousy. My work is how I take revenge, that I try to transmute difficult, painful, and contradictory feelings that disturb me. I allow myself to extrapolate into melodrama and carry out my delusions of revenge, power, fame, and other things that seem impossible. In the process, there are visions of satisfying images that I want to see in the world. Little by little, these visions take shape and acquire texture, sound, and rhythm. Whenever I make a video, I worry about what I want to convey, conceptually and aesthetically, but I never really know where I want to go until I get there.

I always start from a real discomfort inflicting me at that specific moment. It can be the fear of dying and being forgotten, the anger I feel at disgusting men, or jealousy. My work is how I take revenge, that I try to transmute difficult, painful, and contradictory feelings that disturb me. I allow myself to extrapolate into melodrama and carry out my delusions of revenge, power, fame, and other things that seem impossible. In the process, there are visions of satisfying images that I want to see in the world. Little by little, these visions take shape and acquire texture, sound, and rhythm. Whenever I make a video, I worry about what I want to convey, conceptually and aesthetically, but I never really know where I want to go until I get there.

Laura Fraiz. Film still of No Es Una Novela.

[TT]

Tell us a little about your ideas for the Pivô Satellite project. What are your plans?

Tell us a little about your ideas for the Pivô Satellite project. What are your plans?

[LF]

For Pivô Satellite, I made a video called No Es Una Novela, divided into three episodes. As in a soap opera, each episode ends at the climax to make you want to see what will happen next. This work tells the story of when I was followed and filmed by a man, but I managed to steal his camera and retrieve the footage he took of me. I used this footage in the video, followed by a narration that reveals my internal path during this process, from terror to fascination, from the initial shock of such a violent invasion to the latent desire to expose these images—perhaps it is as a way to gain control over them.

For Pivô Satellite, I made a video called No Es Una Novela, divided into three episodes. As in a soap opera, each episode ends at the climax to make you want to see what will happen next. This work tells the story of when I was followed and filmed by a man, but I managed to steal his camera and retrieve the footage he took of me. I used this footage in the video, followed by a narration that reveals my internal path during this process, from terror to fascination, from the initial shock of such a violent invasion to the latent desire to expose these images—perhaps it is as a way to gain control over them.

NEW MEMESEUM (2020)

@newmemeseum was created at the end of July 2020. It is an anonymous Instagram profile that addresses, with humor and irony, situations in the Brazilian art and cultural field.

@newmemeseum was created at the end of July 2020. It is an anonymous Instagram profile that addresses, with humor and irony, situations in the Brazilian art and cultural field.

Dissemination: courtesy of New Memeseum.

[TT]

Understanding humor and criticism as catalysts for the New Memeseum production, how do you see the boundary between fiction and reality? What would be the role of irony in this limit (if it exists)?

Understanding humor and criticism as catalysts for the New Memeseum production, how do you see the boundary between fiction and reality? What would be the role of irony in this limit (if it exists)?

[NM]

In our view, the boundaries between reality and fiction are very thin, especially in arts. We prefer to think of ways to tell stories and, in them, there is not really a separation between these opposites. They are probably not even opposites. If we think about art histories, those who write them are people. And people make choices: they include some productions and leave others out. Their decisions are based on the 'reality' they can observe—which, for someone else, can be understood as fiction or deception. No narrative framing does without its authors, their point of view, the issues inherent to writing (because writing stories also implies aesthetic and stylistic choices), and a personal observation of the context itself. Art is debating the rewriting of art history – making it art historIES, made by other authors, from other standpoints. However, we believe that it would also be interesting to rethink the way these new narratives are - and will be - written because some vices tend to repeat themselves, such as, for example, the recurrence of the hero figure. Some heroes are being taken down and replaced by new ones. A narrative that has the hero as the protagonist always presupposes war and, consequently, colonialism. When referring to prehistory in the essay The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction, Ursula K. Le Guin comments that: 'story not only has Action, it has a Hero. Heroes are powerful. Before you know it, the men and women in the wild-oat patch and their kids and the skills of the makers and the thoughts of the thoughtful and the songs of the singers are all part of it, have all been pressed into service in the tale of the Hero. But it isn't their story. It's his.' Perhaps, art historiography has always been working in the service of this type of narrative. It is very difficult to get away from that because most Western narratives – from books to series and movies – are structured in this logic. In this sense, we try to think of fiction as a basket. Within that container, there is no hierarchy. As we deposit things inside, they mix, and everything can live together. It is just like art, which cannot simply be displaced from life to be placed on a pedestal. It is inside that basket, mixing with a bunch of other things. As Le Guin argues: 'the Hero does not look well in this bag. He needs a stage or a pedestal or a pinnacle. You put him in a bag, and he looks like a rabbit, like a potato.'

In our view, the boundaries between reality and fiction are very thin, especially in arts. We prefer to think of ways to tell stories and, in them, there is not really a separation between these opposites. They are probably not even opposites. If we think about art histories, those who write them are people. And people make choices: they include some productions and leave others out. Their decisions are based on the 'reality' they can observe—which, for someone else, can be understood as fiction or deception. No narrative framing does without its authors, their point of view, the issues inherent to writing (because writing stories also implies aesthetic and stylistic choices), and a personal observation of the context itself. Art is debating the rewriting of art history – making it art historIES, made by other authors, from other standpoints. However, we believe that it would also be interesting to rethink the way these new narratives are - and will be - written because some vices tend to repeat themselves, such as, for example, the recurrence of the hero figure. Some heroes are being taken down and replaced by new ones. A narrative that has the hero as the protagonist always presupposes war and, consequently, colonialism. When referring to prehistory in the essay The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction, Ursula K. Le Guin comments that: 'story not only has Action, it has a Hero. Heroes are powerful. Before you know it, the men and women in the wild-oat patch and their kids and the skills of the makers and the thoughts of the thoughtful and the songs of the singers are all part of it, have all been pressed into service in the tale of the Hero. But it isn't their story. It's his.' Perhaps, art historiography has always been working in the service of this type of narrative. It is very difficult to get away from that because most Western narratives – from books to series and movies – are structured in this logic. In this sense, we try to think of fiction as a basket. Within that container, there is no hierarchy. As we deposit things inside, they mix, and everything can live together. It is just like art, which cannot simply be displaced from life to be placed on a pedestal. It is inside that basket, mixing with a bunch of other things. As Le Guin argues: 'the Hero does not look well in this bag. He needs a stage or a pedestal or a pinnacle. You put him in a bag, and he looks like a rabbit, like a potato.'

[TT]

Although the distinction between highbrow and lowbrow culture is blurred, how do you understand each other within the institutional hierarchy? Imagining a utopian scenario where it would be possible to break this hierarchy, how do you think the work of the New Memeseum would develop? [NM] We do not yet have an answer to this question because we try to work from what is offered to us. We are not used to working with the utopian because we prefer to be open to the transformations that may occur along the way. As such, profile work can take many forms and develop in many different ways.

Although the distinction between highbrow and lowbrow culture is blurred, how do you understand each other within the institutional hierarchy? Imagining a utopian scenario where it would be possible to break this hierarchy, how do you think the work of the New Memeseum would develop? [NM] We do not yet have an answer to this question because we try to work from what is offered to us. We are not used to working with the utopian because we prefer to be open to the transformations that may occur along the way. As such, profile work can take many forms and develop in many different ways.

Dissemination: courtesy of New Memeseum.

[TT]

Tell us a little about your ideas for the Pivô Satellite project. What are your plans?

Tell us a little about your ideas for the Pivô Satellite project. What are your plans?

[NM]

Mysterious peacock / Gorgeous bird / All is mystery / In your flights / May I fly like this / So many skies like that / Many stories / Would I tell / Mysterious peacock / Gorgeous bird / All is mystery / In your flights / May I fly like this / So many skies like that / Many stories / Would I tell / Mysterious peacock / In this tail / Opened as a fan / Keep me a child / Of everlasting games / Spare me the shame / Of dying so young / So many things / I still want to see / Mysterious peacock / Gorgeous bird / All is mystery / In your flights / May I fly like this / So many skies like that / Many stories / Would I tell / Mysterious peacock / Gorgeous bird / In the dark…

Mysterious peacock / Gorgeous bird / All is mystery / In your flights / May I fly like this / So many skies like that / Many stories / Would I tell / Mysterious peacock / Gorgeous bird / All is mystery / In your flights / May I fly like this / So many skies like that / Many stories / Would I tell / Mysterious peacock / In this tail / Opened as a fan / Keep me a child / Of everlasting games / Spare me the shame / Of dying so young / So many things / I still want to see / Mysterious peacock / Gorgeous bird / All is mystery / In your flights / May I fly like this / So many skies like that / Many stories / Would I tell / Mysterious peacock / Gorgeous bird / In the dark…

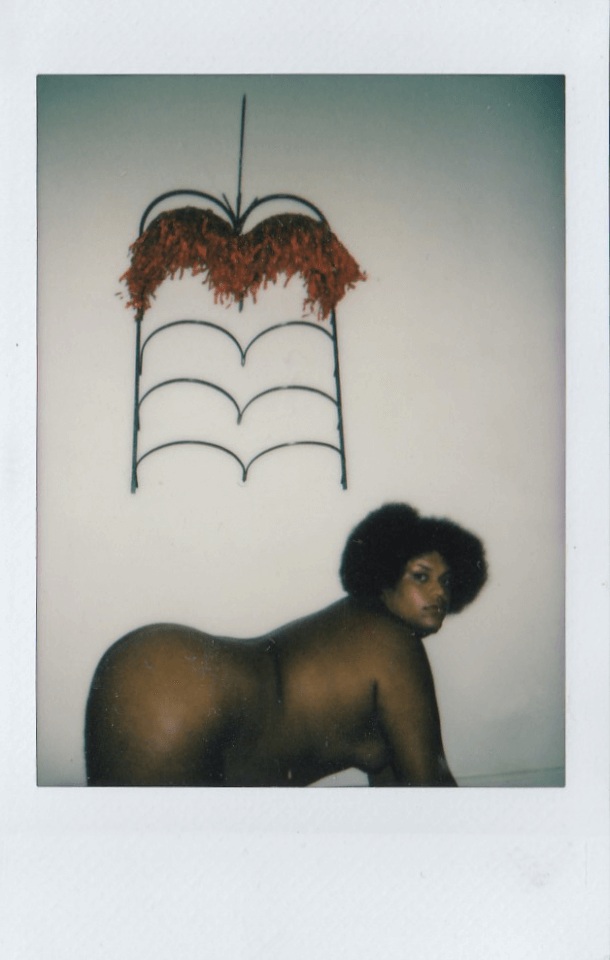

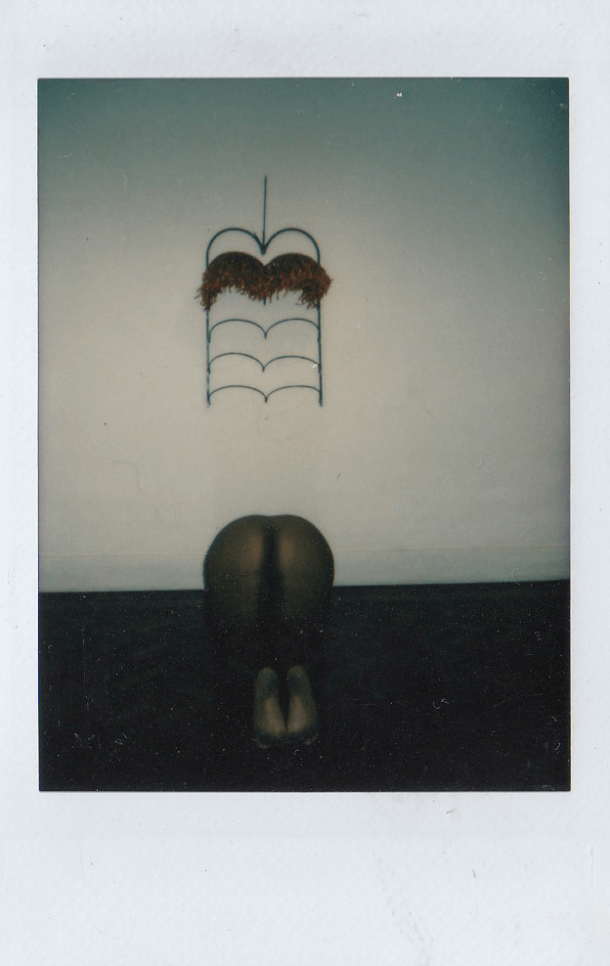

VENTURA PROFANA (Salvador / Bahia, 1993)

Daughter of mother Bahia's mysterious innards, from where arteries of living water abound and sustain life in faith. Ventura Profana prophesies the multiplication and abundance of black, indigenous, and transvestite lives. She cuts through the mist: erotic, atomic, she makes the red her religion. Indoctrinated in Baptist churches, she is a missionary pastor, evangelist singer, writer, composer, and visual artist, whose practice is rooted in researching the implications and methodologies of Deuteronomism in Brazil and abroad through the dissemination of neo-Pentecostal churches. The daisies' oils, pythons, and Regina descend powerfully down the paths until flooding her with desire: anointing her. She praises, like the digging of a wax-and-rust-licked dagger into Pharisees' hearts.

Daughter of mother Bahia's mysterious innards, from where arteries of living water abound and sustain life in faith. Ventura Profana prophesies the multiplication and abundance of black, indigenous, and transvestite lives. She cuts through the mist: erotic, atomic, she makes the red her religion. Indoctrinated in Baptist churches, she is a missionary pastor, evangelist singer, writer, composer, and visual artist, whose practice is rooted in researching the implications and methodologies of Deuteronomism in Brazil and abroad through the dissemination of neo-Pentecostal churches. The daisies' oils, pythons, and Regina descend powerfully down the paths until flooding her with desire: anointing her. She praises, like the digging of a wax-and-rust-licked dagger into Pharisees' hearts.

[TT]

Your production makes evident the chasm between you and the traditional church, as well as the countless similarities that unite you to the gospel. What are the elements of this abyss that you think enhance your work? Likewise, what are the similarities that drive you?

Your production makes evident the chasm between you and the traditional church, as well as the countless similarities that unite you to the gospel. What are the elements of this abyss that you think enhance your work? Likewise, what are the similarities that drive you?

[VP]

I find it difficult to speak of a traditional church knowing the vastness and complexity of liturgical, ecclesiastical, and epistemological practices that make up and characterize a series of Christian denominations that could be read as traditional, but which are certainly not homogeneous. What I explore is the abyss between art—its system and market—and the immensity and depth of Evangelicalism's processes and exercises throughout history until now. Such processes allowed me to experience artmaking since childhood, whether through singing, acting, or creating projected images for the congregation. To me, this abyss looks more like a wall, built, and expanded both by churches in relation to contemporary art and by the traditional artistic system with congregational knowledge/practices. Given this, what my production underlines is the abyss between my transmuted black body and the necropolitical government of the lord of lords—the main supplier, enthusiast, and beneficiary of the project to build and crystallize this wall as well as so many others. The gospel is the groove that enables me to live prophetically abundant even if persecuted and naturalized in an immeasurable valley of countless dry bones, made a pilgrim in the desert both by the art industry and by the conventional spaces of the Abrahamic religions. This gospel is the contradiction—it is the spreading, believing, and sowing of good news, even in captivity.

I find it difficult to speak of a traditional church knowing the vastness and complexity of liturgical, ecclesiastical, and epistemological practices that make up and characterize a series of Christian denominations that could be read as traditional, but which are certainly not homogeneous. What I explore is the abyss between art—its system and market—and the immensity and depth of Evangelicalism's processes and exercises throughout history until now. Such processes allowed me to experience artmaking since childhood, whether through singing, acting, or creating projected images for the congregation. To me, this abyss looks more like a wall, built, and expanded both by churches in relation to contemporary art and by the traditional artistic system with congregational knowledge/practices. Given this, what my production underlines is the abyss between my transmuted black body and the necropolitical government of the lord of lords—the main supplier, enthusiast, and beneficiary of the project to build and crystallize this wall as well as so many others. The gospel is the groove that enables me to live prophetically abundant even if persecuted and naturalized in an immeasurable valley of countless dry bones, made a pilgrim in the desert both by the art industry and by the conventional spaces of the Abrahamic religions. This gospel is the contradiction—it is the spreading, believing, and sowing of good news, even in captivity.

[TT]

The idea of robbery and death is evident in your production. Do you see a relationship between them? [VP] It is curious because my work is fervently established on what can never be stolen or forgotten even though history and reality, prescribed in the colonial disciplinary linearity, conspire and accumulate on shoulders like mine only the extortionate desire for annihilation. In my poetics, what shines is the life I invoke and proclaim.

The idea of robbery and death is evident in your production. Do you see a relationship between them? [VP] It is curious because my work is fervently established on what can never be stolen or forgotten even though history and reality, prescribed in the colonial disciplinary linearity, conspire and accumulate on shoulders like mine only the extortionate desire for annihilation. In my poetics, what shines is the life I invoke and proclaim.

Ventura Profana. Photo Mirella Ferreira.

[TT]

Tell us a bit about your ideas for the Pivô Satellite project? What are your plans?

Tell us a bit about your ideas for the Pivô Satellite project? What are your plans?

[VP]

It was through the precious commitment of all the members of our congregation—fueled by the fact that our church in spirit already possesses the magnitude, power, and glory of a strong and united nation, yet still pilgrimaging in the arduous task of building our temple—that we were able to build our faith, the walls and lay the cornerstone, which is Jesus. Soon, after an intense fundraising campaign and the Pivô Satellite's support, we inaugurated the headquarters of the Congregação Pentecostal Missão de Vida [Pentecostal Life Mission Congregation].

It was through the precious commitment of all the members of our congregation—fueled by the fact that our church in spirit already possesses the magnitude, power, and glory of a strong and united nation, yet still pilgrimaging in the arduous task of building our temple—that we were able to build our faith, the walls and lay the cornerstone, which is Jesus. Soon, after an intense fundraising campaign and the Pivô Satellite's support, we inaugurated the headquarters of the Congregação Pentecostal Missão de Vida [Pentecostal Life Mission Congregation].

Compartilhar

Whatsapp |Telegram |Mail |Facebook |Twitter