Jaime Lauriano

[TT]

I always start by asking what has been going through people's heads in the past few years or what they are developing, but as I already know about the project you are working on now, I think we will end up going towards that direction anyway.

I always start by asking what has been going through people's heads in the past few years or what they are developing, but as I already know about the project you are working on now, I think we will end up going towards that direction anyway.

[JL]

For the last three years, I have been working on a project with the historians Lilia Schwarcz and Flávio Gomes, a book published by Companhia das Letras called the Enciclopédia Negra (Black Encyclopaedia), in which we biographed more than 550 black personalities, from the fourteenth century to the nineteenth century. We invited thirty-six artists to make 100 portraits of these people, most of whom had no biographies nor any images of them. The book brings together personalities like religious, insurrections' and revolts' leaders and others like women who fought for their family's freedom. The portraits were produced by artists already established in the Brazilian contemporary art scene, but also by new ones that have not yet had their first solo show. During this process, we partnered with the Pinacoteca do Estado de São Paulo to donate these portraits, which will be exhibited next month at the institution and become part of its collection afterward. It was very interesting because I had never organized a book before, it was the first time I had worked in the publishing market, and the cool thing is that the project started very shy. Initially, we were going to make thirty portraits, 200 entries, but as we began to present the project to some institutions, we ended up gaining new partners. Almost halfway through the process, we obtained financial support from the Instituto Ibirapitanga, a foundation created by Walther Moreira Salles. Such contribution allowed us to grow until the size we are today: a 300-page book with 550 biographies and 100 portraits. Also, halfway through the project, I had the opportunity to present it to Jochen Volz, Pinacoteca's director. I showed him the idea and the desire to intervene in the institution's collection, which does not have many portraits of black people. He accepted it straight away with great enthusiasm, and Pinacoteca also joined as project partners, from the conception to the development of the exhibition. In addition to making these biographies, we managed to form a network of artists, from ten initially to thirty-six at the end. Thus, the project gained new layers. We are already thinking about producing a second volume, which would focus not only on Brazilians but also on transatlantic characters from all over America, Africa, and Europe. That is the project I have been most involved in in the last three years. Yet, I was at the same time doing my exhibitions, focusing on my artist works properly speaking, despite believing that the Black Encyclopedia is also part of it since I am an intellectual artist, not only a studio artist. I began to understand that all the works I was producing and selling within the art circuit were a way to finance these long-term projects, which did not give me sufficient funds to make a living. What I understood, and began to disseminate, was that all those around me encouraging my work - like my art dealer or collectors - were part of this network, which I call the network of building an anti-racist pedagogy. So, from the moment someone bought my work, I began to encourage the creation of this and other projects that I have been doing. Currently, I am studying aspects of kids' games and colonization as part of my artistic research. I bring together toys I have found in Portugal, where I live, which are more than simple toys but advertisements for children addressing the colonization problem. So, I started to study the feasibility of these projects through the creation of a network that understands collectors and institutions not as individuals or places of art commercialization and exhibition but rather as a support and financing network. Hence, the book is basically the project that I have dedicated myself the most to in the last three years, in addition to three individual exhibitions, at MAC-Niterói, Fundação Joaquim Nabuco, and Sesc Vila Mariana, which also addressed the colonization problem. I am beginning to understand how my work takes place in multimedia and beyond the artistic realm. The pandemic was super challenging but also interesting to work in this way, organizing, guiding, and following other artists to produce the book content but also for thinking about the internet and how we can create biographical videos for YouTube. I am currently trying to think about how to expand access to the works and content I create.

For the last three years, I have been working on a project with the historians Lilia Schwarcz and Flávio Gomes, a book published by Companhia das Letras called the Enciclopédia Negra (Black Encyclopaedia), in which we biographed more than 550 black personalities, from the fourteenth century to the nineteenth century. We invited thirty-six artists to make 100 portraits of these people, most of whom had no biographies nor any images of them. The book brings together personalities like religious, insurrections' and revolts' leaders and others like women who fought for their family's freedom. The portraits were produced by artists already established in the Brazilian contemporary art scene, but also by new ones that have not yet had their first solo show. During this process, we partnered with the Pinacoteca do Estado de São Paulo to donate these portraits, which will be exhibited next month at the institution and become part of its collection afterward. It was very interesting because I had never organized a book before, it was the first time I had worked in the publishing market, and the cool thing is that the project started very shy. Initially, we were going to make thirty portraits, 200 entries, but as we began to present the project to some institutions, we ended up gaining new partners. Almost halfway through the process, we obtained financial support from the Instituto Ibirapitanga, a foundation created by Walther Moreira Salles. Such contribution allowed us to grow until the size we are today: a 300-page book with 550 biographies and 100 portraits. Also, halfway through the project, I had the opportunity to present it to Jochen Volz, Pinacoteca's director. I showed him the idea and the desire to intervene in the institution's collection, which does not have many portraits of black people. He accepted it straight away with great enthusiasm, and Pinacoteca also joined as project partners, from the conception to the development of the exhibition. In addition to making these biographies, we managed to form a network of artists, from ten initially to thirty-six at the end. Thus, the project gained new layers. We are already thinking about producing a second volume, which would focus not only on Brazilians but also on transatlantic characters from all over America, Africa, and Europe. That is the project I have been most involved in in the last three years. Yet, I was at the same time doing my exhibitions, focusing on my artist works properly speaking, despite believing that the Black Encyclopedia is also part of it since I am an intellectual artist, not only a studio artist. I began to understand that all the works I was producing and selling within the art circuit were a way to finance these long-term projects, which did not give me sufficient funds to make a living. What I understood, and began to disseminate, was that all those around me encouraging my work - like my art dealer or collectors - were part of this network, which I call the network of building an anti-racist pedagogy. So, from the moment someone bought my work, I began to encourage the creation of this and other projects that I have been doing. Currently, I am studying aspects of kids' games and colonization as part of my artistic research. I bring together toys I have found in Portugal, where I live, which are more than simple toys but advertisements for children addressing the colonization problem. So, I started to study the feasibility of these projects through the creation of a network that understands collectors and institutions not as individuals or places of art commercialization and exhibition but rather as a support and financing network. Hence, the book is basically the project that I have dedicated myself the most to in the last three years, in addition to three individual exhibitions, at MAC-Niterói, Fundação Joaquim Nabuco, and Sesc Vila Mariana, which also addressed the colonization problem. I am beginning to understand how my work takes place in multimedia and beyond the artistic realm. The pandemic was super challenging but also interesting to work in this way, organizing, guiding, and following other artists to produce the book content but also for thinking about the internet and how we can create biographical videos for YouTube. I am currently trying to think about how to expand access to the works and content I create.

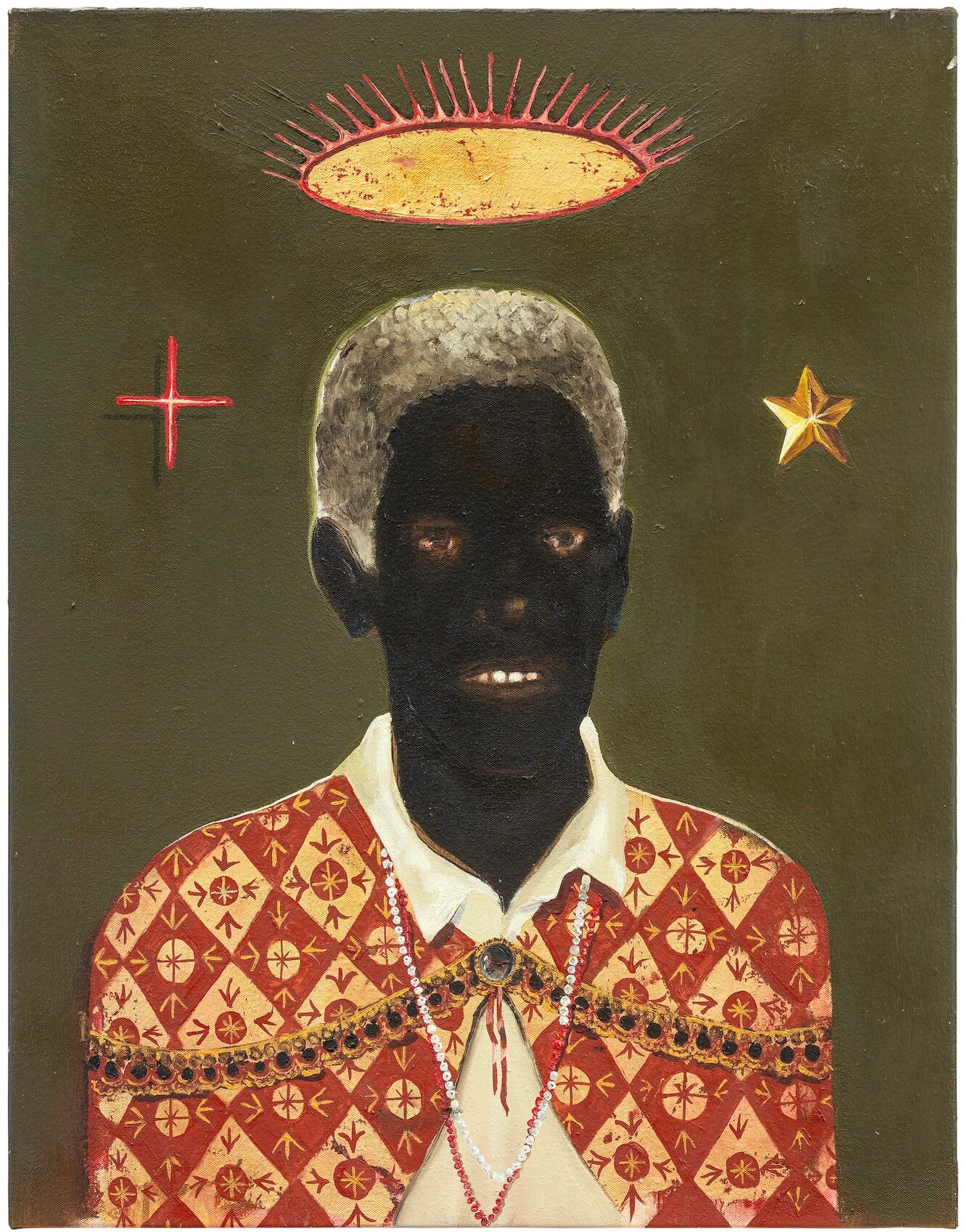

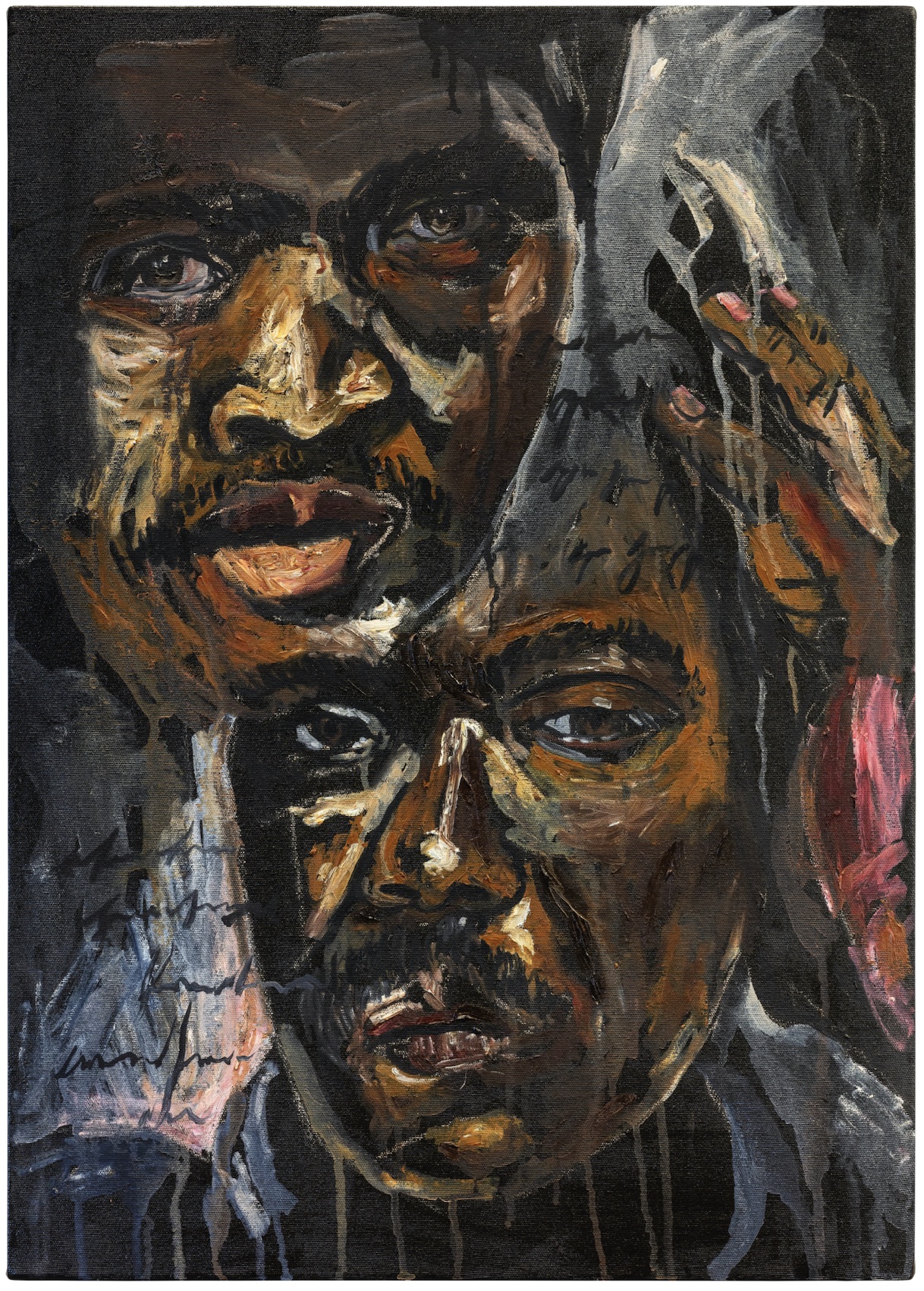

Salustia, por Moisés Patrício. Crédito: Reprodução de Filipe Berndt

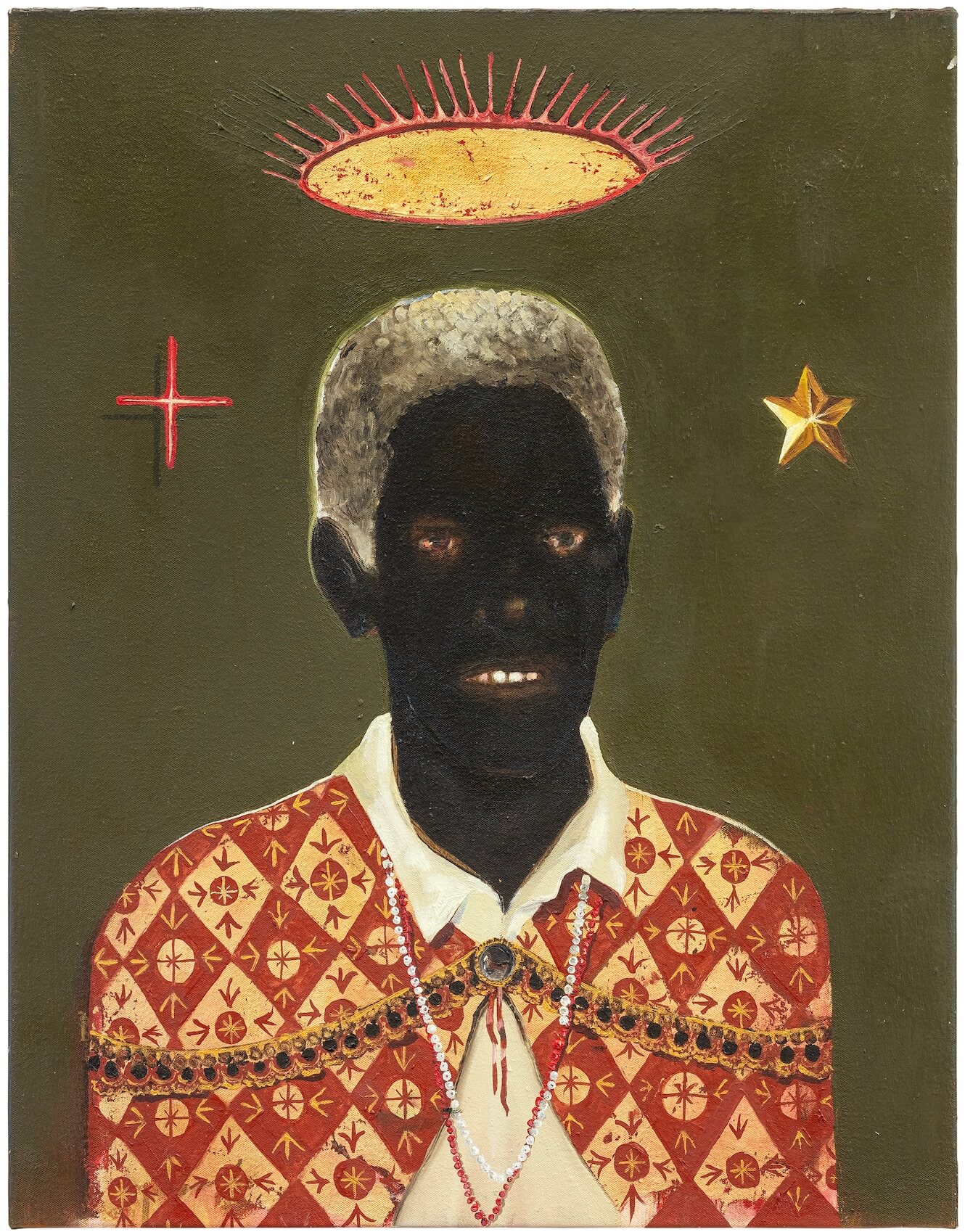

Chico Rey, por Antonio Obá. Crédito: Reprodução de Filipe Berndt

[TT]

And how did the Enciclopédia Negra project come about? How was it born?

And how did the Enciclopédia Negra project come about? How was it born?

[JL]

Lilia Schwarcz and Flávio Gomes had already been developing this project for a couple of years. In 2017, I did the book cover for their Dicionário da Escravidão e Liberdade (Dictionary of Slavery and Freedom), and we had to travel around Brazil to take part in book launch events. During this period, we bonded a lot because I brought in some facets concerning the importance of thinking about images - and that touched upon an investigation that Lilia was already developing. I used to say that the images were also like entries, both in the Enciclopédia Negra and in the Dicionário da Escravidão e Liberdade. They invited me to join them, and I was like, 'Wow, how am I going to contribute? These are two great intellectuals...' I almost declined the invitation because it was a lot of responsibility, but they argued, 'no, there is no way you will not accept it; you are already part of the project.'

Lilia Schwarcz and Flávio Gomes had already been developing this project for a couple of years. In 2017, I did the book cover for their Dicionário da Escravidão e Liberdade (Dictionary of Slavery and Freedom), and we had to travel around Brazil to take part in book launch events. During this period, we bonded a lot because I brought in some facets concerning the importance of thinking about images - and that touched upon an investigation that Lilia was already developing. I used to say that the images were also like entries, both in the Enciclopédia Negra and in the Dicionário da Escravidão e Liberdade. They invited me to join them, and I was like, 'Wow, how am I going to contribute? These are two great intellectuals...' I almost declined the invitation because it was a lot of responsibility, but they argued, 'no, there is no way you will not accept it; you are already part of the project.'

[TT]

It was not an invitation, you were summoned, then.

It was not an invitation, you were summoned, then.

[JL]

Exactly. I said, 'okay, let's do it, but give me some time to think and bring some ideas.' I read the project and said we had to expand and could not stick with a restricted number of portraits. That was when I thought about having more portraits and donating them to a public museum so we could make a direct intervention in history. It is very significant to have these portraits in the Pinacoteca because hundreds of years from now, other people will be researching them. They immediately accepted and said that my part in organizing the book was already guaranteed, and they gave me the challenge of expanding the public's access to the material. That was when I started to make the articulation between institutions, artists, and authors.

Exactly. I said, 'okay, let's do it, but give me some time to think and bring some ideas.' I read the project and said we had to expand and could not stick with a restricted number of portraits. That was when I thought about having more portraits and donating them to a public museum so we could make a direct intervention in history. It is very significant to have these portraits in the Pinacoteca because hundreds of years from now, other people will be researching them. They immediately accepted and said that my part in organizing the book was already guaranteed, and they gave me the challenge of expanding the public's access to the material. That was when I started to make the articulation between institutions, artists, and authors.

[TT]

So, you started softly, then you went head-on…

So, you started softly, then you went head-on…

[JL]

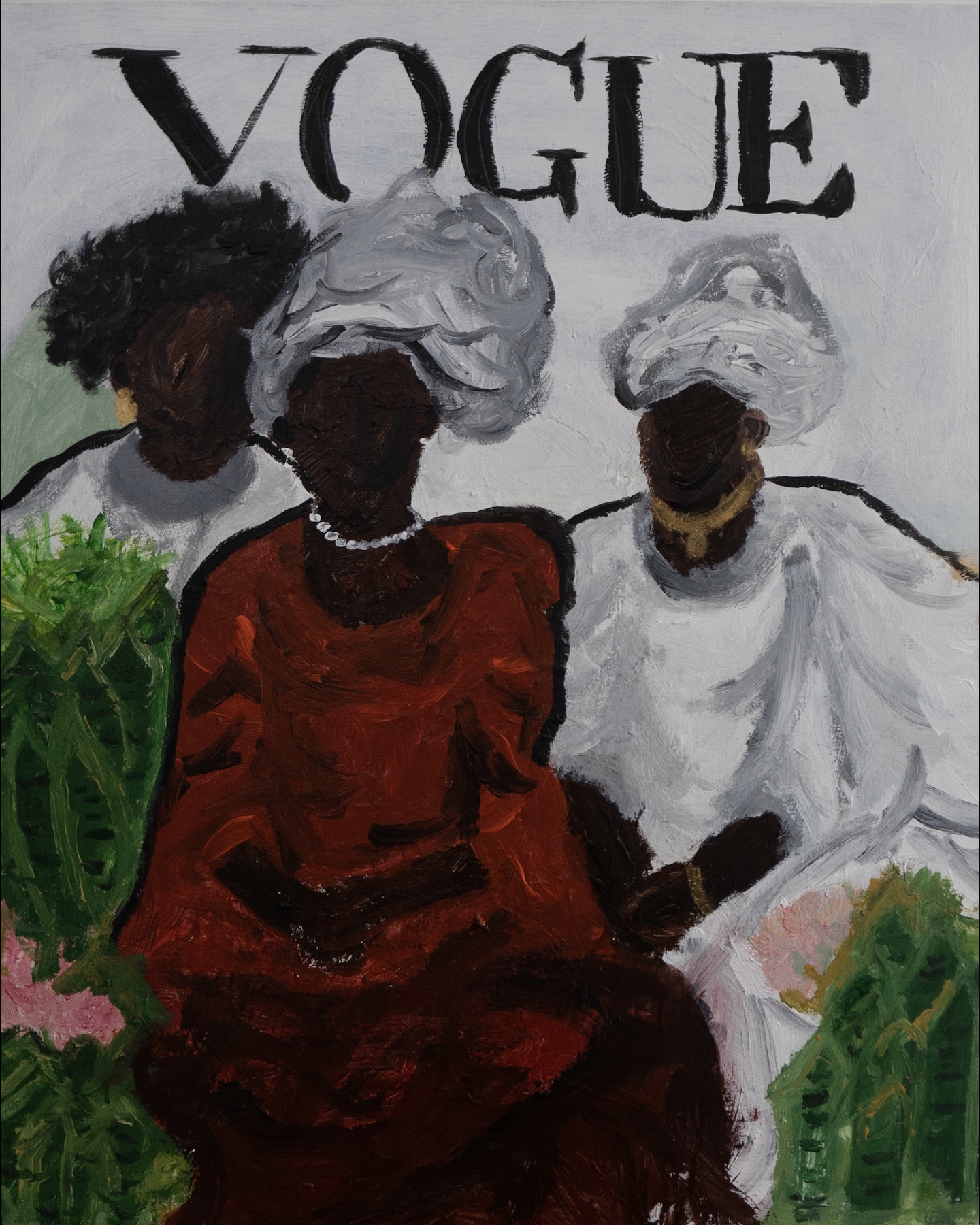

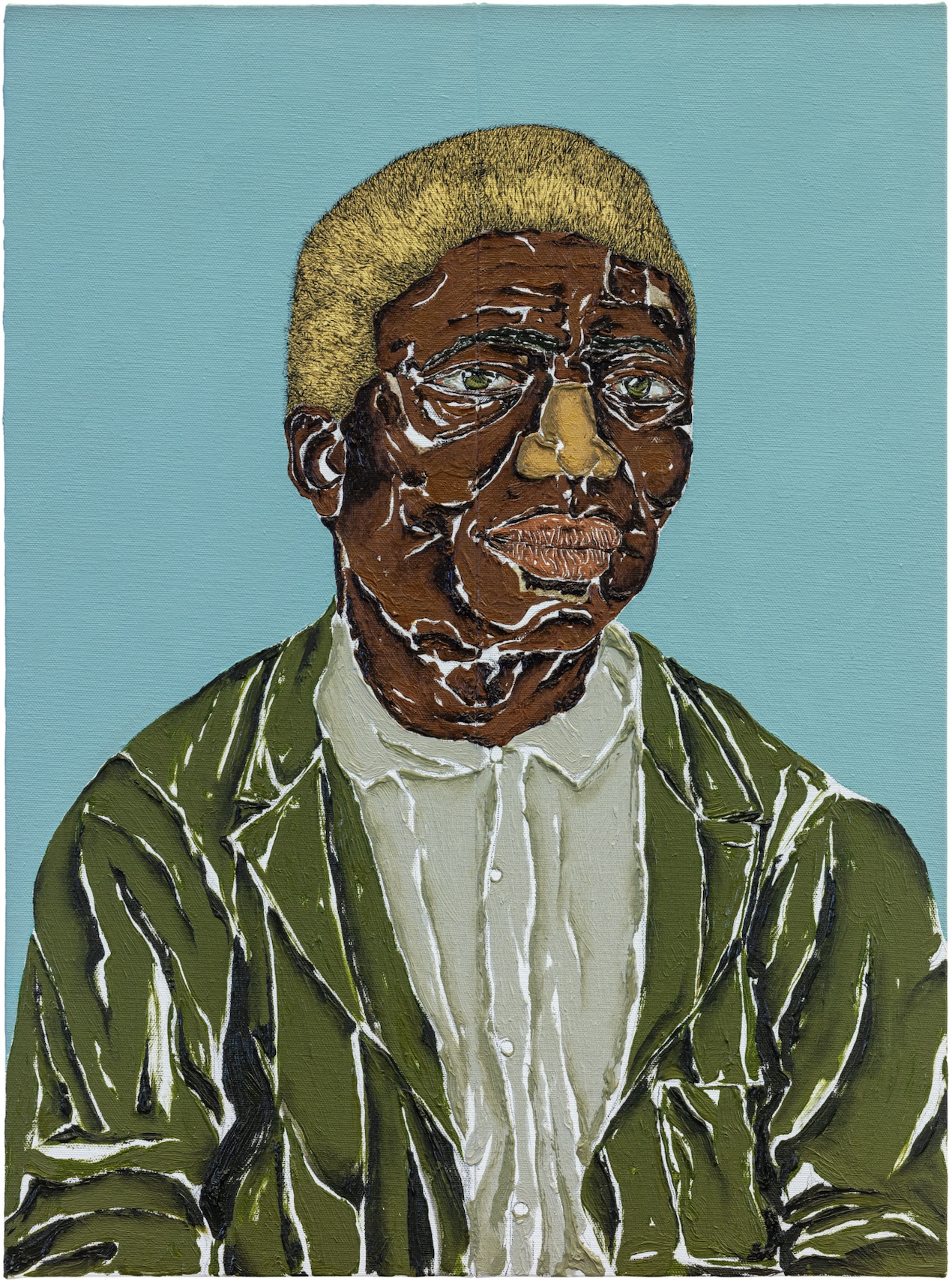

Yes, it was at a time when I was thinking a lot about how images can be an element of transhistorical reflection between the past and the present. So, I brought that idea to the project to elicit the question of what a portrait is since we were talking about people who did not have access to that medium. The idea was not necessarily to produce realistic portraits or a faithful reproduction of how that person would be, but that the artists could create what they imagined, even if completely abstract. We, then, brought to the Encyclopedia the necessity of reviewing the portrait canon in art history, which is one of the most classic and ancient ones. It was very interesting to reflect on how we could talk about other worldviews, other forms of representation.

Yes, it was at a time when I was thinking a lot about how images can be an element of transhistorical reflection between the past and the present. So, I brought that idea to the project to elicit the question of what a portrait is since we were talking about people who did not have access to that medium. The idea was not necessarily to produce realistic portraits or a faithful reproduction of how that person would be, but that the artists could create what they imagined, even if completely abstract. We, then, brought to the Encyclopedia the necessity of reviewing the portrait canon in art history, which is one of the most classic and ancient ones. It was very interesting to reflect on how we could talk about other worldviews, other forms of representation.

A Iyamis grandes mães ancestrais, por Nadia Taquary. Crédito: Reprodução de Filipe Berndt.

[TT]

I was even going to ask about that; what was the support of these portraits? What was the approach like with the people who were going to do the portraits? Did you introduce the person who would be portrayed and have a conversation or read the material produced and the artist was free to produce? Are there any support and technical limitations, or is it open?

I was even going to ask about that; what was the support of these portraits? What was the approach like with the people who were going to do the portraits? Did you introduce the person who would be portrayed and have a conversation or read the material produced and the artist was free to produce? Are there any support and technical limitations, or is it open?

[JL]

It has been a year or so since we got in touch with the artists who were going to do the portraits, and we gave them the first version of the biographies. The only restriction was that they would have a maximum size of 50x80cm for editing and exhibition reasons. The technique was totally free, ranging from drawing to sculpture, photography, collage, video, or photo performance. The intention was to let the guest artist create their own interpretation of what that person would be. We did not interfere.

It has been a year or so since we got in touch with the artists who were going to do the portraits, and we gave them the first version of the biographies. The only restriction was that they would have a maximum size of 50x80cm for editing and exhibition reasons. The technique was totally free, ranging from drawing to sculpture, photography, collage, video, or photo performance. The intention was to let the guest artist create their own interpretation of what that person would be. We did not interfere.

[TT]

I think this adds a lot to the construction of an imaginary...

I think this adds a lot to the construction of an imaginary...

[JL]

Yes, they do not look like each other. They are totally different and very particular.

Yes, they do not look like each other. They are totally different and very particular.

[TT]

And how did the construction of the biography happen? [JL] Each text has an average length of two pages maximum. The research was done in primary sources, police records, etc. In Brazil, we do not have a wealth of primary sources, but we have official records. Thus, we did some of the research in books, where we could find some brief biographies but also in obituary records, slave purchase and sale records – that was a vast hydrographic investigation carried out over six years. There were more than a thousand biographies, and we had to select a little more than half - we had to edit and polish until we arrived at an accessible text, not too hermetic and closed, and we opted for a shorter format. We also have all the data and research sources available to anyone who wants to delve into a given person beyond what is in the book.

And how did the construction of the biography happen? [JL] Each text has an average length of two pages maximum. The research was done in primary sources, police records, etc. In Brazil, we do not have a wealth of primary sources, but we have official records. Thus, we did some of the research in books, where we could find some brief biographies but also in obituary records, slave purchase and sale records – that was a vast hydrographic investigation carried out over six years. There were more than a thousand biographies, and we had to select a little more than half - we had to edit and polish until we arrived at an accessible text, not too hermetic and closed, and we opted for a shorter format. We also have all the data and research sources available to anyone who wants to delve into a given person beyond what is in the book.

Vitória, Catarina e Josefa, por Elian Almeida. Crédito: Reprodução de Filipe Berndt.

[TT]

I wonder if this was the biggest challenge, bringing these sources together and making them one in the sense of minimally representing a person.

I wonder if this was the biggest challenge, bringing these sources together and making them one in the sense of minimally representing a person.

[JL]

It was a challenge to create a portrait of these people, as faithful as possible, with the material we had and put the readers closer to those in the biographies. It was a big challenge in terms of editing and organization. I had never done biography; it was a very difficult and intense thing, but I think the result was good - we are super happy. The book went to the printer and will be launched on March 29th. At the exhibition, scheduled for April, there will be shorter versions of the biographies and more portraits than in the book. It will be 106 works of 97 biographed people, whereas the book has thirty-six, one portrait by each artist.

It was a challenge to create a portrait of these people, as faithful as possible, with the material we had and put the readers closer to those in the biographies. It was a big challenge in terms of editing and organization. I had never done biography; it was a very difficult and intense thing, but I think the result was good - we are super happy. The book went to the printer and will be launched on March 29th. At the exhibition, scheduled for April, there will be shorter versions of the biographies and more portraits than in the book. It will be 106 works of 97 biographed people, whereas the book has thirty-six, one portrait by each artist.

[TT]

How did the selection of these guest artists happen?

How did the selection of these guest artists happen?

[JL]

I follow some of these artists. Some are already well established on the art circuit; others I follow through Instagram. But I also asked for references to people I know who also research black artists. It was really activating a network, capillary, going to exhibitions, doing field research, getting in touch with what is happening today beyond the Rio-São Paulo axis. In addition to creating a balance between those artists who already have projection and those who do not, we have a geographic division in all regions of Brazil, with more women than men - this was an initial premise. It was a work of putting together a puzzle, and it was interesting because we managed to activate, even within us, other ways of seeing art. There are graffiti artists, illustrators, not only people who are part of the contemporary art institutional circuit.

I follow some of these artists. Some are already well established on the art circuit; others I follow through Instagram. But I also asked for references to people I know who also research black artists. It was really activating a network, capillary, going to exhibitions, doing field research, getting in touch with what is happening today beyond the Rio-São Paulo axis. In addition to creating a balance between those artists who already have projection and those who do not, we have a geographic division in all regions of Brazil, with more women than men - this was an initial premise. It was a work of putting together a puzzle, and it was interesting because we managed to activate, even within us, other ways of seeing art. There are graffiti artists, illustrators, not only people who are part of the contemporary art institutional circuit.

[TT]

I have issues with the idea of a panorama, but the essence of it pleases me in the sense of having this multiplicity, taking into account some assumptions such as the majority of women, artists without much projection, the division on the map... [JL] It was one of our premises since we are talking about Brazil really representing Brazil.

I have issues with the idea of a panorama, but the essence of it pleases me in the sense of having this multiplicity, taking into account some assumptions such as the majority of women, artists without much projection, the division on the map... [JL] It was one of our premises since we are talking about Brazil really representing Brazil.

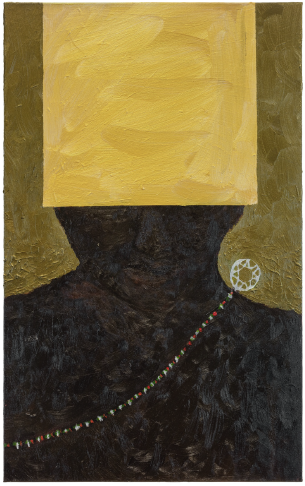

Daniel de Viana, por Dalton Paula

[TT]

And how did you choose the people to write their biographies?

And how did you choose the people to write their biographies?

[JL]

We try to get away from the common places, get out of São Paulo, Rio, Bahia, and Minas Gerais, which are the most talked-about places when it comes to slavery, gender, geographical, and historical divisions. We did not focus only on the enslavement period but also the post-emancipation period. In the book's introduction, we set a starting date, which was 1888, but not an end date. That is why, from the post-emancipation period until today, we are not talking about full emancipation. We also did not select people by occupation, that is, our selection does not only include enslaved people but sportspeople, journalists, doctors, architects, engineers, artists as a way to draw a richer panorama of the complexity of the black community history in Brazil. We did not want to talk only about enslaved people. We also wanted to discuss that if people came to Brazil enslaved in the so-called tumbeiros, they brought with them their religions, crafts, arts, medicines. We are talking about the complexity that the deportation and kidnapping of people to work in situations of enslavement created. We want to show that the history of slavery in Brazil is not constituted only of enslaved people.

We try to get away from the common places, get out of São Paulo, Rio, Bahia, and Minas Gerais, which are the most talked-about places when it comes to slavery, gender, geographical, and historical divisions. We did not focus only on the enslavement period but also the post-emancipation period. In the book's introduction, we set a starting date, which was 1888, but not an end date. That is why, from the post-emancipation period until today, we are not talking about full emancipation. We also did not select people by occupation, that is, our selection does not only include enslaved people but sportspeople, journalists, doctors, architects, engineers, artists as a way to draw a richer panorama of the complexity of the black community history in Brazil. We did not want to talk only about enslaved people. We also wanted to discuss that if people came to Brazil enslaved in the so-called tumbeiros, they brought with them their religions, crafts, arts, medicines. We are talking about the complexity that the deportation and kidnapping of people to work in situations of enslavement created. We want to show that the history of slavery in Brazil is not constituted only of enslaved people.

Mathias Henrique da Silvia e Faustino da Silva, por Panmela Castro. Crédito: Reprodução de Filipe Berndt.

[TT]

This project is amazing. I am looking forward to reading the book. Where will it be disseminated? How will the sale be?

This project is amazing. I am looking forward to reading the book. Where will it be disseminated? How will the sale be?

[JL]

It is already on the pre-sale on bookstores and will be in both physical and digital formats. The first edition has 9000 books, it is a big edition, but we still plan to do a second one soon. It is available on the Companhia das Letras website, on Amazon, Livraria Cultura, Livraria da Travessa, all online bookstores.

It is already on the pre-sale on bookstores and will be in both physical and digital formats. The first edition has 9000 books, it is a big edition, but we still plan to do a second one soon. It is available on the Companhia das Letras website, on Amazon, Livraria Cultura, Livraria da Travessa, all online bookstores.

[TT]

You mentioned that you live between Brazil and Portugal. Are you already thinking about disseminating the project outside Brazil? How do you feel this idea is received in Portugal?

You mentioned that you live between Brazil and Portugal. Are you already thinking about disseminating the project outside Brazil? How do you feel this idea is received in Portugal?

[JL]

We are thinking about the international dissemination, both of the book and the exhibition. Portugal would be easier because of the Portuguese language. First, the idea is to travel with the exhibition across Brazil in 2022, having at least one event in at least one city in each region of the country, as it will be an important year where we will celebrate the Bicentennial of Independence and the Centenary of the Modern Art Week. Then we thought about promoting it outside Brazil. I think it is an important exhibition, and it should be shown in other places. In Portugal, it is difficult to talk about colonization; it is a self-esteem issue for them. I gave an interview just before coming to Brazil for Jornal Público, which is the biggest newspaper in Portugal; its special section on Culture was interviewing Brazilian artists who were living in the country. The answer I give you to this question is the same one I gave them. They have an ego issue with colonization. It serves to affirm the important role they played in the world, how great a nation they were. That is clear in the formation of people and cities. They have monuments to the discovery of the Americas, monuments to discovering heroes. At the same time, there are few initiatives to question this colonial past, and, often, these questions come from people from the African diaspora. Brazilians, Mozambicans, Angolans, Cape Verdeans, and all members of the Community of Portuguese Language Countries (CPLC) are bringing a necessary discussion to Portugal, but it is still very incipient. Portugal is not an open country; it is not part of the global discussions on decoloniality; it is not a present and pressing discussion in the country. I think we have an opportunity to point the finger and the discomfort to the fore. In contrast to Brazil, in Portugal, the discomfort with the colonial past has to be exposed.

We are thinking about the international dissemination, both of the book and the exhibition. Portugal would be easier because of the Portuguese language. First, the idea is to travel with the exhibition across Brazil in 2022, having at least one event in at least one city in each region of the country, as it will be an important year where we will celebrate the Bicentennial of Independence and the Centenary of the Modern Art Week. Then we thought about promoting it outside Brazil. I think it is an important exhibition, and it should be shown in other places. In Portugal, it is difficult to talk about colonization; it is a self-esteem issue for them. I gave an interview just before coming to Brazil for Jornal Público, which is the biggest newspaper in Portugal; its special section on Culture was interviewing Brazilian artists who were living in the country. The answer I give you to this question is the same one I gave them. They have an ego issue with colonization. It serves to affirm the important role they played in the world, how great a nation they were. That is clear in the formation of people and cities. They have monuments to the discovery of the Americas, monuments to discovering heroes. At the same time, there are few initiatives to question this colonial past, and, often, these questions come from people from the African diaspora. Brazilians, Mozambicans, Angolans, Cape Verdeans, and all members of the Community of Portuguese Language Countries (CPLC) are bringing a necessary discussion to Portugal, but it is still very incipient. Portugal is not an open country; it is not part of the global discussions on decoloniality; it is not a present and pressing discussion in the country. I think we have an opportunity to point the finger and the discomfort to the fore. In contrast to Brazil, in Portugal, the discomfort with the colonial past has to be exposed.

[TT]

I am not even surprised. It is not like we Brazilians have no problems with our colonial past because it is still present in our lives. But I think it must be complicated there, especially concerning self-esteem; it must affect the ego and self-affirmation.

I am not even surprised. It is not like we Brazilians have no problems with our colonial past because it is still present in our lives. But I think it must be complicated there, especially concerning self-esteem; it must affect the ego and self-affirmation.

[JL]

Yes, for sure. I am working now with a Brazilian artist friend called Igor Vidor, who also lives in Porto. I was doing field research and came across the Monopoly game. In Portugal, they have one called Odisseia dos Descobrimentos (Discoveries Odyssey), in which instead of buying a building, you buy a captaincy, you buy cocoa from Mozambique, coffee from Brazil, gold from Cape Verde. I am shooting a video where I read the game rules and the official texts about colonization while the tokens move around on the board. We want to release it next year, on the Bicentennial of Brazil's Independence.

Yes, for sure. I am working now with a Brazilian artist friend called Igor Vidor, who also lives in Porto. I was doing field research and came across the Monopoly game. In Portugal, they have one called Odisseia dos Descobrimentos (Discoveries Odyssey), in which instead of buying a building, you buy a captaincy, you buy cocoa from Mozambique, coffee from Brazil, gold from Cape Verde. I am shooting a video where I read the game rules and the official texts about colonization while the tokens move around on the board. We want to release it next year, on the Bicentennial of Brazil's Independence.

[TT]

Wow! Is this game as famous as Monopoly?

Wow! Is this game as famous as Monopoly?

[JL]

It is a new game, sold in toy stores. It is in places like that, of recognition, that colonization operates. The work I am developing puts the finger on the colonial wound and proposes we get out of our comfort zone to see what is happening around the world. There is also the self-esteem question: they are one of the poorest countries in Europe, but they are still part of Europe; they still see themselves in this place.

It is a new game, sold in toy stores. It is in places like that, of recognition, that colonization operates. The work I am developing puts the finger on the colonial wound and proposes we get out of our comfort zone to see what is happening around the world. There is also the self-esteem question: they are one of the poorest countries in Europe, but they are still part of Europe; they still see themselves in this place.

[TT]

That is ironic.

That is ironic.

[JL]

It is part of the Old World, but it is economically worse than Brazil. Today, Brazil has much more influence in Portugal than the other way around, so these things contribute to the Portuguese low self-esteem, who insist on making it clear that we are outsiders. While this is violent, it is interesting to show that this behavior is ridiculous. This video is to show these attitudes and how to live in this melancholy, this nostalgia of the colonization when the whole world is discussing decolonial processes, hold the Portuguese down.

It is part of the Old World, but it is economically worse than Brazil. Today, Brazil has much more influence in Portugal than the other way around, so these things contribute to the Portuguese low self-esteem, who insist on making it clear that we are outsiders. While this is violent, it is interesting to show that this behavior is ridiculous. This video is to show these attitudes and how to live in this melancholy, this nostalgia of the colonization when the whole world is discussing decolonial processes, hold the Portuguese down.

A Feiticeira Mascarada, por Sonia Gomes. Crédito: Reprodução de Filipe Berndt.

Reis Malunguinho, por Micaela Cyrino. Crédito: Reprodução de Filipe Berndt.

[TT]

Why and how did you decide to go there?

Why and how did you decide to go there?

[JL]

I had never been to Portugal, which is part of my research on the Atlantic triangle. My ex-wife was going to do a master's degree in Porto, and I thought it would be good for researching, seeing colonization from another point of view, combining the useful with the pleasant dimension, a professional with personal aspect. It was very important because I was able to do field research, go to the archives, see the monuments, talk to the Portuguese about colonization and get the feedback I gave you now. Now, I live between there and here because Brazil also feeds my creativity.

I had never been to Portugal, which is part of my research on the Atlantic triangle. My ex-wife was going to do a master's degree in Porto, and I thought it would be good for researching, seeing colonization from another point of view, combining the useful with the pleasant dimension, a professional with personal aspect. It was very important because I was able to do field research, go to the archives, see the monuments, talk to the Portuguese about colonization and get the feedback I gave you now. Now, I live between there and here because Brazil also feeds my creativity.

[TT]

It is a project that does not come to an end, I suppose. But do you have future plans?

It is a project that does not come to an end, I suppose. But do you have future plans?

[JL]

I want to finish and release this film on the game; about this colonial nostalgia, and next year I will complete fifteen years of working as an artist. For 2022, I am editing a retrospective book of my production and preparing an exhibition about the last fifteen years. Probably an exhibition in Portugal too, with the research I have been doing there since I arrived.

I want to finish and release this film on the game; about this colonial nostalgia, and next year I will complete fifteen years of working as an artist. For 2022, I am editing a retrospective book of my production and preparing an exhibition about the last fifteen years. Probably an exhibition in Portugal too, with the research I have been doing there since I arrived.

[TT]

How do you imagine this solo show? How do you visualize it?

How do you imagine this solo show? How do you visualize it?

[JL]

I am developing it with curator Hélio Menezes. We are going to do it in two parts. The first would take place last year, during the Bienal, but due to the pandemic we were unable to open, so we decided to do both in 2022. One part would be with archive materials and the other more focused on my work, but we put the two together. I wanted to bring archives from institutes that keep Brazilian memory, like Afro Museum, so we also invited other artists to collaborate within the exhibition. We planning something that goes beyond the conventional retrospective exhibition, almost like a major intervention. Its name comes from an excerpt of a song by Torquato Neto and Gilberto Gil, Marginália II, which says that Aqui é o fim do mundo (here is the end of the world)—this is the title of the exhibition. Death is one of the most present elements in my work, not only as an end but as a possibility of rebirth, of resistance. It comes from a memory key; it is working on that leap between memory and the end within an exhibition that has the name ‘Aqui é o fim do mundo’. The song says, 'here is the end of the world, here is the end of the world,' in this sense of the end that carries a beginning. Thinking about the Death card in the tarot, it is death, but also a new beginning. The Obaluaê also brings death and healing at the same time. We are thinking about this duality of life and death, which is even something we talk about in the Encyclopedia—'if we talk about death here, here we also talk about life.'

I am developing it with curator Hélio Menezes. We are going to do it in two parts. The first would take place last year, during the Bienal, but due to the pandemic we were unable to open, so we decided to do both in 2022. One part would be with archive materials and the other more focused on my work, but we put the two together. I wanted to bring archives from institutes that keep Brazilian memory, like Afro Museum, so we also invited other artists to collaborate within the exhibition. We planning something that goes beyond the conventional retrospective exhibition, almost like a major intervention. Its name comes from an excerpt of a song by Torquato Neto and Gilberto Gil, Marginália II, which says that Aqui é o fim do mundo (here is the end of the world)—this is the title of the exhibition. Death is one of the most present elements in my work, not only as an end but as a possibility of rebirth, of resistance. It comes from a memory key; it is working on that leap between memory and the end within an exhibition that has the name ‘Aqui é o fim do mundo’. The song says, 'here is the end of the world, here is the end of the world,' in this sense of the end that carries a beginning. Thinking about the Death card in the tarot, it is death, but also a new beginning. The Obaluaê also brings death and healing at the same time. We are thinking about this duality of life and death, which is even something we talk about in the Encyclopedia—'if we talk about death here, here we also talk about life.'

Compartilhar

Whatsapp |Telegram |Mail |Facebook |Twitter