Nacional Trovoa

[TT]

What is the collective, and how did it come about?

What is the collective, and how did it come about?

[NT]

The Levante Nacional TROVOA is a collective of racialized visual artists and curators from the five Brazilian regions (North, Northeast, Midwest, Southeast, and South). So far, the collective has mapped eleven States, including Amazonas, Bahia, Ceará, Espírito Santo, Goiás, Mato Grosso, Maranhão, Pará, Pernambuco, Rio de Janeiro, and São Paulo. Founded in 2017 in Rio de Janeiro city, Levante Nacional TROVOA was born from the initial concerns of four young women, and it claims urgency in the discussion about the art system in Brazil, with special attention to the visibility and insertion of cis and trans racialized artists in this circuit. As a collective, we aspire to highlight our non-hegemonic productions that derive from racial intersections passing through indigenous, black, and Asian backgrounds.

The Levante Nacional TROVOA is a collective of racialized visual artists and curators from the five Brazilian regions (North, Northeast, Midwest, Southeast, and South). So far, the collective has mapped eleven States, including Amazonas, Bahia, Ceará, Espírito Santo, Goiás, Mato Grosso, Maranhão, Pará, Pernambuco, Rio de Janeiro, and São Paulo. Founded in 2017 in Rio de Janeiro city, Levante Nacional TROVOA was born from the initial concerns of four young women, and it claims urgency in the discussion about the art system in Brazil, with special attention to the visibility and insertion of cis and trans racialized artists in this circuit. As a collective, we aspire to highlight our non-hegemonic productions that derive from racial intersections passing through indigenous, black, and Asian backgrounds.

[TT]

What has changed since the collective's birth until today?

What has changed since the collective's birth until today?

[NT]

We are non-white women artists, curators, and art educators—including Asian and indigenous women, as well as non-binary, transsexuals, and transvestites—who interact together in a network. All over Brazil, these women began to propose spheres of debate, lectures, and exhibitions with racialized women artists who do not fit into the whiteness spectrum. Today, we are approximately 180 participants and forty active articulators who propose activities in their communities according to the cities' context and needs. Since the hegemonic art circuit does not include our bodies and productions, creating the network is, and becomes, a brand, Trovoa, which works as a representative and can be present in different places simultaneously. That allows us to tell our narratives, generating visibility for the collective.

We are non-white women artists, curators, and art educators—including Asian and indigenous women, as well as non-binary, transsexuals, and transvestites—who interact together in a network. All over Brazil, these women began to propose spheres of debate, lectures, and exhibitions with racialized women artists who do not fit into the whiteness spectrum. Today, we are approximately 180 participants and forty active articulators who propose activities in their communities according to the cities' context and needs. Since the hegemonic art circuit does not include our bodies and productions, creating the network is, and becomes, a brand, Trovoa, which works as a representative and can be present in different places simultaneously. That allows us to tell our narratives, generating visibility for the collective.

[TT]

How do you see the future of the collective?How do you see the future of the collective?

[NT] Nacional Trovoa has been gaining space in the art circuit, especially in São Paulo, where galleries and institutions have paid attention to our movement. We must increasingly look at the collective dimension, as it becomes extremely important to think about our processes and works, especially our subjectivities as racialized artists and curators. Our plan is to continue in constant negotiation with the hegemonic art circuit.

How do you see the future of the collective?How do you see the future of the collective?

[NT] Nacional Trovoa has been gaining space in the art circuit, especially in São Paulo, where galleries and institutions have paid attention to our movement. We must increasingly look at the collective dimension, as it becomes extremely important to think about our processes and works, especially our subjectivities as racialized artists and curators. Our plan is to continue in constant negotiation with the hegemonic art circuit.

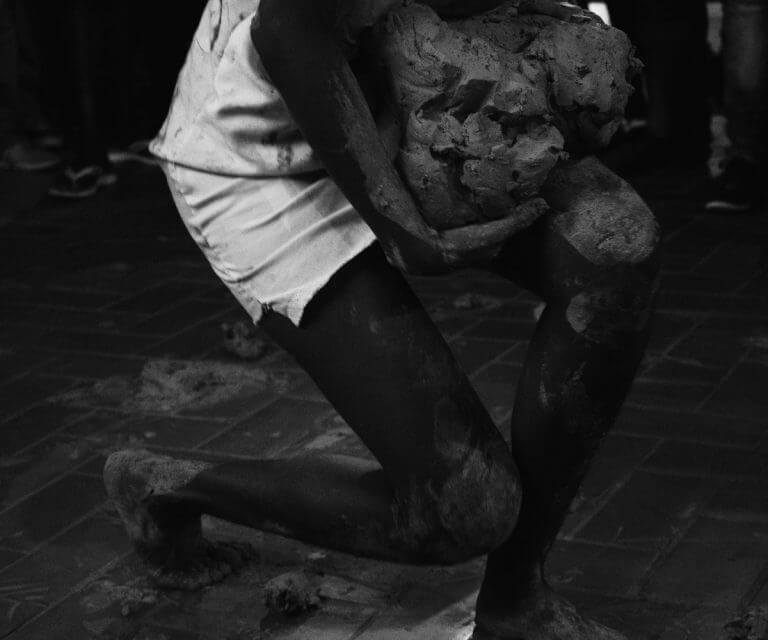

Aline Besouro, Constância, 2020. Técnica mista.

Bárbara Milano, Fotografia Ritual, Huni-Kuin “Circuito dos Pajés”, 2017. NIBU.

[TT]

In your opinion, what is the importance of the decentralization of art?

In your opinion, what is the importance of the decentralization of art?

[NT]

We currently have around forty articulators residing in five regions of the country. Among artists, curators, art educators with different interests, we work through local autonomy. Each regional group or articulator diagnoses the needs of their city in order to design strategies for actions. We work in decentralized scenes to reduce internal borders, revealing discourses immanent to the frontiers. Trovoa organizes artistic fruition actions aiming to bring to the national artistic context the diffusion of content from different regions of Brazil, promoting and stimulating the decentralization of artistic-cultural agenda concentrated mainly in Brazil's south-southeast axis.

We currently have around forty articulators residing in five regions of the country. Among artists, curators, art educators with different interests, we work through local autonomy. Each regional group or articulator diagnoses the needs of their city in order to design strategies for actions. We work in decentralized scenes to reduce internal borders, revealing discourses immanent to the frontiers. Trovoa organizes artistic fruition actions aiming to bring to the national artistic context the diffusion of content from different regions of Brazil, promoting and stimulating the decentralization of artistic-cultural agenda concentrated mainly in Brazil's south-southeast axis.

[TT]

How is the daily experience of a collective formed by cis and trans racialized women from different parts of the country? How does this connection happen?

How is the daily experience of a collective formed by cis and trans racialized women from different parts of the country? How does this connection happen?

[NT]

We are actively connected through online digital platforms. Although many regions have limited internet and high-speed connection access, the virtual environment is the most decentralized and plural, open to opinion and information exchange, which occurs faster than in other spaces.

We are actively connected through online digital platforms. Although many regions have limited internet and high-speed connection access, the virtual environment is the most decentralized and plural, open to opinion and information exchange, which occurs faster than in other spaces.

[TT]

Several artists from the collective are working at SP-Arte How do you see the relationship between the collective and the fair?

[NT] Some of the collective members have already partnered with the fair for some time as editorial collaborators, such as Carolina Laureano, Aline Motta, and Bianca Leite as a docent. Marina Dias Teixeira, responsible for the fair's institutional dimension and the only black woman on the SP-Arte team, invited us. She has been following the Trovoa collective's trajectory for some time and has been contributing to the fair to increase its inclusion of black artists, curators, art educators, and researchers.

Several artists from the collective are working at SP-Arte How do you see the relationship between the collective and the fair?

[NT] Some of the collective members have already partnered with the fair for some time as editorial collaborators, such as Carolina Laureano, Aline Motta, and Bianca Leite as a docent. Marina Dias Teixeira, responsible for the fair's institutional dimension and the only black woman on the SP-Arte team, invited us. She has been following the Trovoa collective's trajectory for some time and has been contributing to the fair to increase its inclusion of black artists, curators, art educators, and researchers.

Bianca Leite, Sem título, da série “Vibrações”, 2020. Pintura, 24 × 32 cm.

[TT]

For you, what are the difficulties in entering the art market? And what is the importance of being part of it?

For you, what are the difficulties in entering the art market? And what is the importance of being part of it?

[NT]

The Fair is an international event, and numerous curators, directors of important institutions, collectors from different countries, participate in it. It also attracts a non-specialized audience, who can get to know a part of the Levante Nacional Trovoa production. Being visible to both audiences is extremely important for the collective's artists, who mostly are outside the art circuit. The collective's participation brings a perspective not always contemplated in commercial events such as art fairs; thus, enriching the SP-Arte Viewing Room in terms of participating projects and proposed parallel art programming.

The Fair is an international event, and numerous curators, directors of important institutions, collectors from different countries, participate in it. It also attracts a non-specialized audience, who can get to know a part of the Levante Nacional Trovoa production. Being visible to both audiences is extremely important for the collective's artists, who mostly are outside the art circuit. The collective's participation brings a perspective not always contemplated in commercial events such as art fairs; thus, enriching the SP-Arte Viewing Room in terms of participating projects and proposed parallel art programming.

Carla Santana, Sem título, da série “Desdobrando fardos”, 2019. Fotografia.

[TT]

What other collectives or artists are your references?

What other collectives or artists are your references?

[NT]

We are a collective with many members, and this question cannot be answered objectively, as each has a background and a trajectory. Generally speaking, we are connected and looking at Afro-diasporic, Amerindian, and dissident artistic productions.

We are a collective with many members, and this question cannot be answered objectively, as each has a background and a trajectory. Generally speaking, we are connected and looking at Afro-diasporic, Amerindian, and dissident artistic productions.

[TT]

If you could choose a space (physical or not) for a collective intervention, which space would it be?

If you could choose a space (physical or not) for a collective intervention, which space would it be?

[NT]

We believe that our bodies—because they are racialized and trans women—are sometimes prohibited from entering institutional spaces. Even though we could exercise our imagination here, I believe that this choice has more to do with a serious negotiation with institutions interested in opening a communication channel where we can talk about decentralization, remuneration, and safe conditions to carry out exquisite work.

We believe that our bodies—because they are racialized and trans women—are sometimes prohibited from entering institutional spaces. Even though we could exercise our imagination here, I believe that this choice has more to do with a serious negotiation with institutions interested in opening a communication channel where we can talk about decentralization, remuneration, and safe conditions to carry out exquisite work.

Cyshimi, Viviane Lee Hsu, “Forever Love”, 2020. Escultura.

[TT]

If possible, I would like each artist to talk a little about their work at the fair. Aline Besouro / [TT] Tell us a little about how you see the relationship between memory and your work. How does it appear in your production?

If possible, I would like each artist to talk a little about their work at the fair. Aline Besouro / [TT] Tell us a little about how you see the relationship between memory and your work. How does it appear in your production?

[AB]

Since I was little, I have been interested in registering, writing, and narrating stories. As a child, I had the habit of cutting out the newspaper and producing new newspapers from the images and words. The relationship I establish with memory in my work comes, in part, from my own memory, mainly from childhood and early adolescence. These references became part of my artistic interest over time, unfolding into the matter I produce. One of these examples talks about my relationship with sewing, which started at the age of five with grandma Elza, but also about my development in drawing. Since I was young, I was always encouraged to draw from the geometrical design due to my father's and mother's love and common interest in math, drawing, and art. Upon entering the artistic study, I identified immediately with the performance processes as a path for my artistic development. The first work I did, where I recognized myself as an artist, involved the construction of soft tissue and red velvet womb where I kept myself inside, gestating until the moment I was born. This self-initiation was directly related to the memory of my birth and the understanding that, at that moment, my role in this world began to unfold.

Since I was little, I have been interested in registering, writing, and narrating stories. As a child, I had the habit of cutting out the newspaper and producing new newspapers from the images and words. The relationship I establish with memory in my work comes, in part, from my own memory, mainly from childhood and early adolescence. These references became part of my artistic interest over time, unfolding into the matter I produce. One of these examples talks about my relationship with sewing, which started at the age of five with grandma Elza, but also about my development in drawing. Since I was young, I was always encouraged to draw from the geometrical design due to my father's and mother's love and common interest in math, drawing, and art. Upon entering the artistic study, I identified immediately with the performance processes as a path for my artistic development. The first work I did, where I recognized myself as an artist, involved the construction of soft tissue and red velvet womb where I kept myself inside, gestating until the moment I was born. This self-initiation was directly related to the memory of my birth and the understanding that, at that moment, my role in this world began to unfold.

Bárbara Milano /

[TT] Tell us a little about the relationship between photography and performance and/or about your Fotografia Ritual (Ritual Photography) project.

[TT] Tell us a little about the relationship between photography and performance and/or about your Fotografia Ritual (Ritual Photography) project.

[BM]

My photographic production originates from the relationship with performativity. The recording of relational art-based works, which I did at the beginning of my career, led me to think about photography in a way that could represent me through someone else's image. I have been mixing languages ever since. In Fotografia Ritual, I look for a way to combine these experiences, and I arrive at the photography's reflection as itself a rite in what concerns the photography's gestures. In this case, the relationship with the idea of rite (in itself performative) is intrinsic, as it refers to photography performed in ayahuasca rituals with native peoples. The research that I develop with this master's begins in 2017, with the Huni Kuin (AC) people, the NIBU network, and the study group on the 'sacred plants of the forest,' which also works in technical, technological, and cultural exchange with the original peoples. In 2020, I presented my work's records at the Zonas de Compensação (Compensation Zones) exhibition, which will have its first online edition, and at the Emergências seminar by post-grad art students at UNESP.

My photographic production originates from the relationship with performativity. The recording of relational art-based works, which I did at the beginning of my career, led me to think about photography in a way that could represent me through someone else's image. I have been mixing languages ever since. In Fotografia Ritual, I look for a way to combine these experiences, and I arrive at the photography's reflection as itself a rite in what concerns the photography's gestures. In this case, the relationship with the idea of rite (in itself performative) is intrinsic, as it refers to photography performed in ayahuasca rituals with native peoples. The research that I develop with this master's begins in 2017, with the Huni Kuin (AC) people, the NIBU network, and the study group on the 'sacred plants of the forest,' which also works in technical, technological, and cultural exchange with the original peoples. In 2020, I presented my work's records at the Zonas de Compensação (Compensation Zones) exhibition, which will have its first online edition, and at the Emergências seminar by post-grad art students at UNESP.

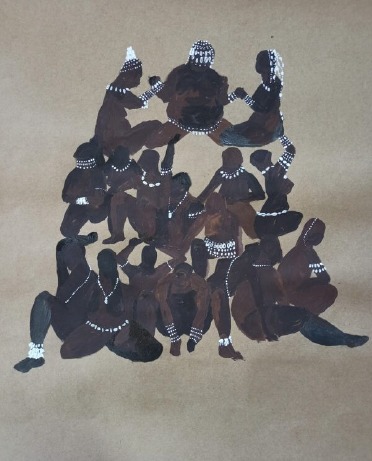

Gabriela Monteiro, “Caminho secreto”, 2019. Pintura, 140 × 170 cm.

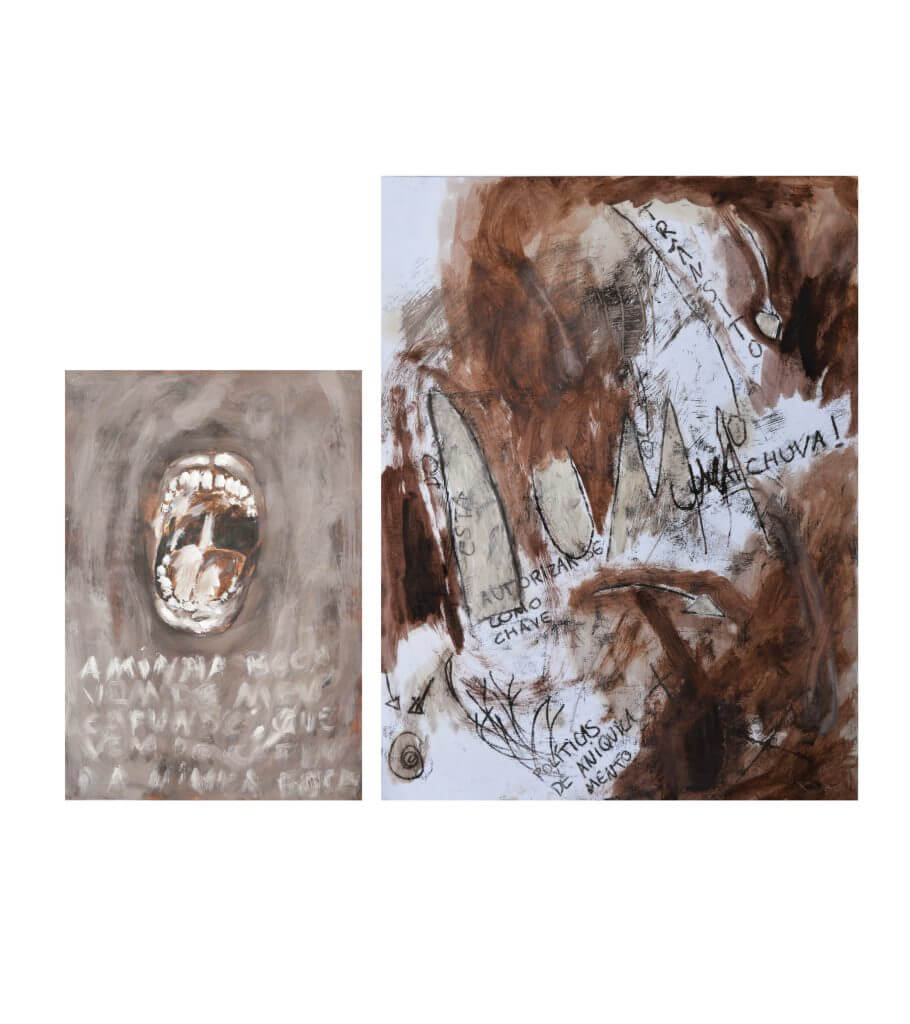

Hariel Revignet, Sem título, 2020. Pintura.

Bianca Leite /

[TT] Talk about repetition in your work and/or comment on the relationship of the materials used with the theme.

[TT] Talk about repetition in your work and/or comment on the relationship of the materials used with the theme.

[BL]

Repetition comes from the desire to create organic forms, giving a greater outlet to unpredictability in abstract painting. I recently started working with watercolor ink, which is a specific ink for heavyweight papers. The movement I make when I am creating reminds me of the fins of fish swimming in the sea, an eternal coming and going. In most watercolors, I insert some India ink stains made with syringes' and needles' squirts, objects often used in hospitals. I draw dotted fine lines with the syringe. The ink stains on the watercolor grow and spread, forming limited spaces in shapes that evoke large craters, earthy terrain seen on Google Earth, or the deepest places in the oceans.

Repetition comes from the desire to create organic forms, giving a greater outlet to unpredictability in abstract painting. I recently started working with watercolor ink, which is a specific ink for heavyweight papers. The movement I make when I am creating reminds me of the fins of fish swimming in the sea, an eternal coming and going. In most watercolors, I insert some India ink stains made with syringes' and needles' squirts, objects often used in hospitals. I draw dotted fine lines with the syringe. The ink stains on the watercolor grow and spread, forming limited spaces in shapes that evoke large craters, earthy terrain seen on Google Earth, or the deepest places in the oceans.

Carla Santana /

[TT] Tell us a little about the relationship with the body in your work, exploring issues such as the subjective-body and the social-body.

[TT] Tell us a little about the relationship with the body in your work, exploring issues such as the subjective-body and the social-body.

[CS]

In my work, the relationship with the body is a primordial structure. I always like to say that we think with our whole body. This axiom symbolizes for me the denial of the western duality where body and mind are disconnected. I understand my corporeality as an expressive intellectual tool, where I absorb things and let them flow. The body is memory, language, beginning, middle, and end. From this place, I start to observe the intrinsic cracks, what comes from the outside and stays within, what is mine and leaves me, what is so deep inside that I cannot see it. I observe how intimacy can unfold into identification and assimilation. I began to highlight as an analytical object the fine line between the social-body and the subjective-body, their conditioning, archetypes, traumas, and experiences. At first, I felt the need to materialize pains and unspeakable questions. I realized that it was a denser moment of searching, questioning, and healing. Afterward, I entered into a more elementary and spiritual understanding of my body. I manifest imaginaries and dreams through installations made with earth, clay, water, and glass. Currently, I feel the need to study unpretentiousness and observation, a kind of existentialist vibe. It makes my process more important than the final product, by a magnifying glass on the 'aesthetics of existence.' All this honoring the hull I inhabit.

In my work, the relationship with the body is a primordial structure. I always like to say that we think with our whole body. This axiom symbolizes for me the denial of the western duality where body and mind are disconnected. I understand my corporeality as an expressive intellectual tool, where I absorb things and let them flow. The body is memory, language, beginning, middle, and end. From this place, I start to observe the intrinsic cracks, what comes from the outside and stays within, what is mine and leaves me, what is so deep inside that I cannot see it. I observe how intimacy can unfold into identification and assimilation. I began to highlight as an analytical object the fine line between the social-body and the subjective-body, their conditioning, archetypes, traumas, and experiences. At first, I felt the need to materialize pains and unspeakable questions. I realized that it was a denser moment of searching, questioning, and healing. Afterward, I entered into a more elementary and spiritual understanding of my body. I manifest imaginaries and dreams through installations made with earth, clay, water, and glass. Currently, I feel the need to study unpretentiousness and observation, a kind of existentialist vibe. It makes my process more important than the final product, by a magnifying glass on the 'aesthetics of existence.' All this honoring the hull I inhabit.

Julliana Araújo, Sem título, da série “Vão”, 2018. Fotografia

Cyshimi - Viviane Lee Hsu /

[TT] Tell us a little about the role the cyber environment plays in your work and/or ancestral relationships it has.

[TT] Tell us a little about the role the cyber environment plays in your work and/or ancestral relationships it has.

[C]

As a transdisciplinary artist, I work with various media, questioning the limits between them, which makes my practice very fluid. I transit between digital and manual, and both influence each other a lot. The digital is very present in my generation. With it, I changed the way I work, organize myself, relate to others, and it mainly formed my repertoire and references. When I create, I start from this repertoire, that is, the digital is always the base and intrinsic to my creations. I have worked with augmented reality, virtual reality, and digital collages. The presence of design in my practices is also very influential. As a Chinese-Brazilian, I research Brazilian and Asian identities as non-white individuals, and these dissident identities influence me a lot. Additionally, I try to research ancestry not only from an affirmative but also from a decolonial perspective. Currently, I have been delving deeper into researching Chinese individuals in Brazil, mainly with my project 1212 – Sorteio de Qipao, a collaborative project with twelve different people throughout the year, reinterpreting and actualizing Qipao clothing through experimental screen printing..

As a transdisciplinary artist, I work with various media, questioning the limits between them, which makes my practice very fluid. I transit between digital and manual, and both influence each other a lot. The digital is very present in my generation. With it, I changed the way I work, organize myself, relate to others, and it mainly formed my repertoire and references. When I create, I start from this repertoire, that is, the digital is always the base and intrinsic to my creations. I have worked with augmented reality, virtual reality, and digital collages. The presence of design in my practices is also very influential. As a Chinese-Brazilian, I research Brazilian and Asian identities as non-white individuals, and these dissident identities influence me a lot. Additionally, I try to research ancestry not only from an affirmative but also from a decolonial perspective. Currently, I have been delving deeper into researching Chinese individuals in Brazil, mainly with my project 1212 – Sorteio de Qipao, a collaborative project with twelve different people throughout the year, reinterpreting and actualizing Qipao clothing through experimental screen printing..

Gabriela Monteiro /

[TT] Talk a little about the influence of ancestry in the construction of the pictorial imaginary.

[TT] Talk a little about the influence of ancestry in the construction of the pictorial imaginary.

[GM]

We went through a process of historical erasure of our families and ancestors. That erasure eliminated my access to my grandparents and their predecessors' histories. I only have my paternal grandmother alive, and when I get in touch with her, I try to rescue those memories. For having access to my family's ancestry only through orality, I try, through listening, to create this imaginary of their paths and lives. And I use painting as a representative platform of these paths, a map I recreate from what I hear and imagine. My paternal grandparents are from Bahia and Alagoas, so I am researching the mixtures they had, their journey to São Paulo, and their return to Bahia. I also try to connect myself with older stories and to think about the journeys from Africa to Brazil. So, basically, my work is about ancestral memories. More specifically, it is about stories of displacements/journeys and how these stories have been repeating in my family and me over time. What marks do these stories have, how do they mark me, how do they repeat themselves through genetics and stories? I seek to raise these questions and understand their non-linearity. My ancestry, which means getting closer to my African ancestry, also brings me closer to African art's history. I usually research a lot about African art, and my references are from there.

We went through a process of historical erasure of our families and ancestors. That erasure eliminated my access to my grandparents and their predecessors' histories. I only have my paternal grandmother alive, and when I get in touch with her, I try to rescue those memories. For having access to my family's ancestry only through orality, I try, through listening, to create this imaginary of their paths and lives. And I use painting as a representative platform of these paths, a map I recreate from what I hear and imagine. My paternal grandparents are from Bahia and Alagoas, so I am researching the mixtures they had, their journey to São Paulo, and their return to Bahia. I also try to connect myself with older stories and to think about the journeys from Africa to Brazil. So, basically, my work is about ancestral memories. More specifically, it is about stories of displacements/journeys and how these stories have been repeating in my family and me over time. What marks do these stories have, how do they mark me, how do they repeat themselves through genetics and stories? I seek to raise these questions and understand their non-linearity. My ancestry, which means getting closer to my African ancestry, also brings me closer to African art's history. I usually research a lot about African art, and my references are from there.

Keila Serruya Sankofa, “Raiz e Patchuli”, 2020. Fotografia.

Hariel Revignet /

[TT] Tell us a little about how you see the tradition of painting and how ancestry acts in the vision of contemporary painting.

[TT] Tell us a little about how you see the tradition of painting and how ancestry acts in the vision of contemporary painting.

[HR]

Elaborating narratives from the image is a powerful element in the creation of collective imaginary. I see the painting, photography, and other artistic languages playing a role in the dispute of counter-narratives, making it possible to revisit Western colonial ideas that distance painting from a collective appropriation without hierarchy. Symbols, bodies, and their synergies' representations activate collective memory. However, images can also foster forgetfulness or a specific historical framing, where only the hegemonic narrative is recognized as 'official' and 'classic.' I decolonize my classic references, understanding how we always act through different technologies of representation within the painting. Ancestry goes beyond linear time-space, so my ancestry is contemporary. It existed and re-exists in the now as well as in the to-come. When I paint Afro-diasporic and Amerindian women, time is crossed by past and future ancestors. As my practices are autobiogeographic,¹ the relationship with Axétetura,² painting-experiences-performance and rituals are part of my daily life and the women who live with me in the terreiro (a religious ground), in the community, in social movements. 1- Professor Manoela dos Anjos Afonso Rodrigues developed this concept. 2- The architect and urban planner Hariel Revignet created this concept.

Elaborating narratives from the image is a powerful element in the creation of collective imaginary. I see the painting, photography, and other artistic languages playing a role in the dispute of counter-narratives, making it possible to revisit Western colonial ideas that distance painting from a collective appropriation without hierarchy. Symbols, bodies, and their synergies' representations activate collective memory. However, images can also foster forgetfulness or a specific historical framing, where only the hegemonic narrative is recognized as 'official' and 'classic.' I decolonize my classic references, understanding how we always act through different technologies of representation within the painting. Ancestry goes beyond linear time-space, so my ancestry is contemporary. It existed and re-exists in the now as well as in the to-come. When I paint Afro-diasporic and Amerindian women, time is crossed by past and future ancestors. As my practices are autobiogeographic,¹ the relationship with Axétetura,² painting-experiences-performance and rituals are part of my daily life and the women who live with me in the terreiro (a religious ground), in the community, in social movements. 1- Professor Manoela dos Anjos Afonso Rodrigues developed this concept. 2- The architect and urban planner Hariel Revignet created this concept.

Juliana Araujo /

[TT] Tell us a little about the relationship between the body and clothing/jewelry/accessories in your work. [JA] I have a degree in Design and have always chosen to get closer to object development. The interesting thing is that, at the beginning of my career in visual arts, I started working with the body and immateriality (installation). Now, I return to my connection with practical research focused on three-dimensionality, the sculpture. Thinking volume as the central form and language in my artistic exercises has deepened and become fundamental for my artistic journey. At SP-Arte, I exhibit Vão, a video art that discusses the absence of black women in spaces and positions of leadership in the Brazilian labor market.

[TT] Tell us a little about the relationship between the body and clothing/jewelry/accessories in your work. [JA] I have a degree in Design and have always chosen to get closer to object development. The interesting thing is that, at the beginning of my career in visual arts, I started working with the body and immateriality (installation). Now, I return to my connection with practical research focused on three-dimensionality, the sculpture. Thinking volume as the central form and language in my artistic exercises has deepened and become fundamental for my artistic journey. At SP-Arte, I exhibit Vão, a video art that discusses the absence of black women in spaces and positions of leadership in the Brazilian labor market.

Mitsy Queiroz, Sem título, 2019. Fotografia.

Keila Serruya Sankofa /

[TT] Tell us a little about how you see the relationship between photography, the body and/or urban space.

[TT] Tell us a little about how you see the relationship between photography, the body and/or urban space.

[K]

Until 2017, my process consisted of directing bodies as my cinematographic narratives, photographs, and/or performance representations. Yet, I recently realized that excluding the possibility of using my body as a narrative structure and support amounts to deny myself. Self-hate is an effective tool in this society that is against the lives of black and indigenous people. In this sense, producing self-esteem is revolutionary. I put myself in the standpoint of the first-person enunciator, and my image states that this body I inhabit is the protagonist of my story. The courage to narrate with my image is recent; it was through the perception and the possibility of rebuilding and putting myself as self-referential that it made me understand the other powers my work has. My school is the street, a priority place when it comes to exhibiting my work or process. It is important to emphasize that I have never held a solo exhibition in a gallery, and given my needs, it cannot happen in the coming years. The STREET and the dialogue I establish with people like me is a way to express my concerns, those that burn my chest like fire. Some things intersect my existence and deny my experience, life, and place as a knowledge producer; this is why I believe that by occupying the city, I can dialogue with all kinds of people, not just artists, curators, or institutions.

Until 2017, my process consisted of directing bodies as my cinematographic narratives, photographs, and/or performance representations. Yet, I recently realized that excluding the possibility of using my body as a narrative structure and support amounts to deny myself. Self-hate is an effective tool in this society that is against the lives of black and indigenous people. In this sense, producing self-esteem is revolutionary. I put myself in the standpoint of the first-person enunciator, and my image states that this body I inhabit is the protagonist of my story. The courage to narrate with my image is recent; it was through the perception and the possibility of rebuilding and putting myself as self-referential that it made me understand the other powers my work has. My school is the street, a priority place when it comes to exhibiting my work or process. It is important to emphasize that I have never held a solo exhibition in a gallery, and given my needs, it cannot happen in the coming years. The STREET and the dialogue I establish with people like me is a way to express my concerns, those that burn my chest like fire. Some things intersect my existence and deny my experience, life, and place as a knowledge producer; this is why I believe that by occupying the city, I can dialogue with all kinds of people, not just artists, curators, or institutions.

Mônica Ventura, “Lei 11.645”, 2020. Pintura, 70 × 65 cm.

Mitsy Queiroz /

[TT] Tell us a little about how you perceive the insertion of objects and words in the photograph.

[TT] Tell us a little about how you perceive the insertion of objects and words in the photograph.

[MQ]

My creative process can slip over the edges of the notebook and swim against the tide; it can stir the soil in search of small memories of the future and collect amulets from everyday life. On the tip of my tongue protests a photograph that salutes the mistake. Passionate about the technical image and its processing, I abandon conventions and consider it the companion for an unpretentious journey through time. I am aware that I throw a stone today to settle problems with my past that is still alive and hanging in a bunch through which time flows without beginning or end. I speak of time because I understand photography as a gateway to these temporal crossings since time is memory, awareness, and knowledge production. I am constantly alluding to image codes and their programming, playing with these logics, and seeking to subvert their norms, whether in analog or digital processing, but continually reflecting these media's particularities and implications in the building of images that have their potential amplified through error. For, I see photography as a sensitive body, incorporating my experiences as a non-binary trans body that seeks alternative rules for all the programming assigned to it. I see it as a place where the inflections of this experience trigger a creative process that also resists the technologies it employs or conducts its wandering construction.

My creative process can slip over the edges of the notebook and swim against the tide; it can stir the soil in search of small memories of the future and collect amulets from everyday life. On the tip of my tongue protests a photograph that salutes the mistake. Passionate about the technical image and its processing, I abandon conventions and consider it the companion for an unpretentious journey through time. I am aware that I throw a stone today to settle problems with my past that is still alive and hanging in a bunch through which time flows without beginning or end. I speak of time because I understand photography as a gateway to these temporal crossings since time is memory, awareness, and knowledge production. I am constantly alluding to image codes and their programming, playing with these logics, and seeking to subvert their norms, whether in analog or digital processing, but continually reflecting these media's particularities and implications in the building of images that have their potential amplified through error. For, I see photography as a sensitive body, incorporating my experiences as a non-binary trans body that seeks alternative rules for all the programming assigned to it. I see it as a place where the inflections of this experience trigger a creative process that also resists the technologies it employs or conducts its wandering construction.

Mônica Ventura /

[TT] Tell us a little about the presence of the object in your work's symbology and composition.

[TT] Tell us a little about the presence of the object in your work's symbology and composition.

[MV]

In general, as a product designer, I am fascinated with producing objects. In my visual artistic productions, the object is often the result of research. To me, it is significant to materialize my research, and I try to do this by detaching myself from the classical formality of the Eurocentric art canon. I have been looking at pre-colonial cultures (African peoples – India's Vedic Culture – Amerindian Culture). In these cosmovisions, the use of specific objects carries a sea of ancestral symbologies, and that is what interests me. I do this decolonial exercise to translate an idea materially.

In general, as a product designer, I am fascinated with producing objects. In my visual artistic productions, the object is often the result of research. To me, it is significant to materialize my research, and I try to do this by detaching myself from the classical formality of the Eurocentric art canon. I have been looking at pre-colonial cultures (African peoples – India's Vedic Culture – Amerindian Culture). In these cosmovisions, the use of specific objects carries a sea of ancestral symbologies, and that is what interests me. I do this decolonial exercise to translate an idea materially.

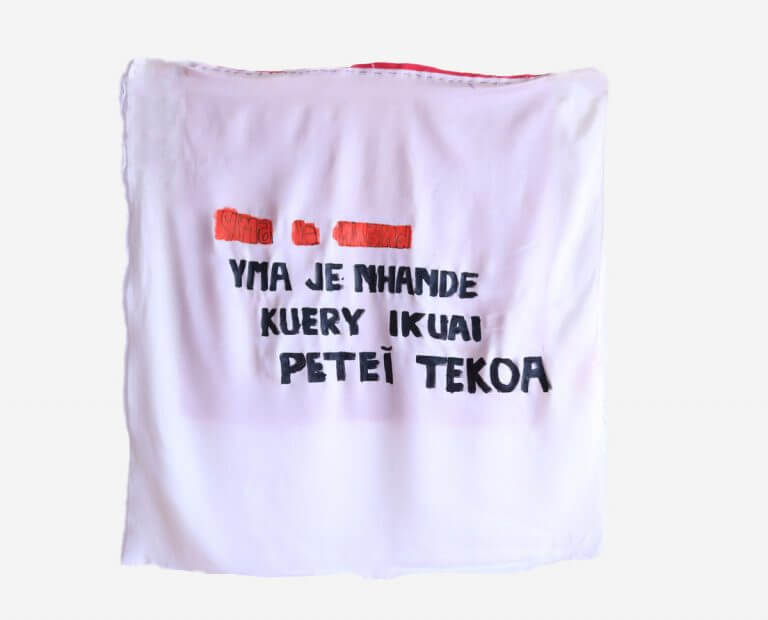

Raylander Mártis dos Anjos, Sem título, da série “Trabalhos escolares”, 2020. Outros, 59 × 42 cm.

Raylander Martis dos Anjos /

[TT] Tell us a little about how you see the world's presence in relation to the body in your work.

[TT] Tell us a little about how you see the world's presence in relation to the body in your work.

[RM]

The head, neck, shoulder, arm, elbow, forearm, wrist, hand, and finger movements in the gesture of writing words poses a very important question: both in its written and oral forms the entire body enacts the spells surrounding the word's craftsmanship with the magical making. In general terms, I want to say that for a word to exist–in the faraway place I come from–, there must be a body presenting itself in the world. In this word-making process, we not only use the body parts I mentioned above but all the muscles, bones, organs, and cells of the whole body, thus configuring a totality of movement. A word dropped into nothingness and without a body would have little effect on our sensible experience. On the other hand, a word thrown in our direction, like a spit, coming from one body towards another, would have a tactile, sonorous, gustatory, and aromatic effect. It would have a psychosomatic effect. To say that the body and the word are related in my practice would be saying little. It would be necessary to talk about a specific combination that I have made between knowledge and the various forms of establishing this knowledge. But it would also be necessary to talk about a constant pirouette movement: both in the body and its magical manifestations in the world.

The head, neck, shoulder, arm, elbow, forearm, wrist, hand, and finger movements in the gesture of writing words poses a very important question: both in its written and oral forms the entire body enacts the spells surrounding the word's craftsmanship with the magical making. In general terms, I want to say that for a word to exist–in the faraway place I come from–, there must be a body presenting itself in the world. In this word-making process, we not only use the body parts I mentioned above but all the muscles, bones, organs, and cells of the whole body, thus configuring a totality of movement. A word dropped into nothingness and without a body would have little effect on our sensible experience. On the other hand, a word thrown in our direction, like a spit, coming from one body towards another, would have a tactile, sonorous, gustatory, and aromatic effect. It would have a psychosomatic effect. To say that the body and the word are related in my practice would be saying little. It would be necessary to talk about a specific combination that I have made between knowledge and the various forms of establishing this knowledge. But it would also be necessary to talk about a constant pirouette movement: both in the body and its magical manifestations in the world.

Sheyla Ayo, Sem título, 2018. Pintura.

Sheyla Ayo /

[TT] Tell us a little about the fabric as support in your work.

[TT] Tell us a little about the fabric as support in your work.

[SA]

The fabric reminds me of a lot of things. My grandmothers and my mother had a lot of intimacy with this material, whether sewing, embroidering, which was the female activity at the time. Cotton itself was a culture that my paternal grandmother reaped a lot when working in the fields when she came from Minas Gerais to Garça, a city in São Paulo's countryside. To provide for the children, she often washed the landowners' clothes and used the fabric to warm up the children or bought fabric pieces to make a dress for some festival. The raw fabric was the material my grandmother bought to make clothes for her children, for ready-made clothes were very expensive. The fabric has weaves, lines, and dialogues with my paintings, shapes, and stories, with the body of my painting. Organic bodies that seek space that deal with unpredictability, like black bodies. We are always in a state of alert; often, the straight line for our trajectory is abruptly interrupted. So, I create, I pray painting, I pray to my ancestors, with great force. I go into a trance for the freedom that has not yet fully come.

The fabric reminds me of a lot of things. My grandmothers and my mother had a lot of intimacy with this material, whether sewing, embroidering, which was the female activity at the time. Cotton itself was a culture that my paternal grandmother reaped a lot when working in the fields when she came from Minas Gerais to Garça, a city in São Paulo's countryside. To provide for the children, she often washed the landowners' clothes and used the fabric to warm up the children or bought fabric pieces to make a dress for some festival. The raw fabric was the material my grandmother bought to make clothes for her children, for ready-made clothes were very expensive. The fabric has weaves, lines, and dialogues with my paintings, shapes, and stories, with the body of my painting. Organic bodies that seek space that deal with unpredictability, like black bodies. We are always in a state of alert; often, the straight line for our trajectory is abruptly interrupted. So, I create, I pray painting, I pray to my ancestors, with great force. I go into a trance for the freedom that has not yet fully come.

Compartilhar

Whatsapp |Telegram |Mail |Facebook |Twitter